In the time since I left trapeze school, I’ve had some incredible ‘continuing education’ experiences in strength and conditioning and I’ve also been spending my days working as a personal trainer at a gym. It’s one of the best ‘corporate’ gyms I’ve ever encountered and I’ve learned A LOT. My heart still belongs to circus though, so pretty much everything I’ve learned in the time that I’ve been there, I’ve also viewed through a circus lens. With that in mind, I’d like to tell you a bit about the world of fitness, personal training and strength and conditioning.

First, a definition of terms. Personal trainers can be found in a variety of venues and typically, they work one-on-one with people I like to think of as everyday athletes. (They also sometimes work with small groups of two to four). Far and away the biggest reason why people seek out a personal trainer is to lose weight. It’s actually a rather large industry (he says like anyone reading isn’t acutely aware of just how colossal the weight-loss industry is…).

Out there, in the world of fitness, there are personal trainers and there are personal trainers. In general, it’s a field with a pretty low barrier to entry: to become a certified personal trainer typically doesn’t require much in the way of prior knowledge or experience. Almost regardless of the initial certification, what distinguishes the best from the rest is a dogged pursuit of continued education alongside of experience. I’m inclined to further specify that the quality of the continuing education also matters.

In my most recent job interview, there was a practical component wherein we were given the opportunity to do a movement analysis with a deep overhead squat and then we did a case study that required us to build a workout program and then explain the rationale for our exercise choices. I have to say, if it were me five to ten years ago as a relatively new trainer, I would have been absolutely lost: I would have had no idea what to look for in a deep overhead squat and my exercise choices were largely based on how challenging I thought they would be. Sometimes I grouped them according to push or pull…but even then, I was still building workouts based on individual muscle groups… I might just summarize this thought by saying that I’m grateful for having been exposed to some incredible coaches.

Defining what I mean by Strength and Conditioning as a field will help to clarify how to figure out what constitutes quality in terms of education. Strength and Conditioning Coaches generally work with athletes and their mandate is to help athletes to improve athletic performance. Actually, the first priority of a strength coach is to do no harm. Improving performance technically comes second.

And this is where it gets interesting. In settings where people are particularly concerned with performance outcomes, understanding how and why an athlete might be more or less prone to injury—in particular the overuse kind—demands looking deeper. No longer is it ok to just plow ahead with doing heavy bench presses, squats and deadlifts. No longer it is good enough to follow a bodybuilding approach to improving movement capacity.

It’s in a strength and conditioning setting where there is more likely to be a team approach to performance enhancement: strength coaches collaborate with physical therapists and doctors and nutritionists and, well, the actual coach for the particular sport the individual athletes participate in.

The strength and conditioning facility where I was received my certification as a functional strength coach is a remarkable one. Located in a suburb of Boston, it is run by one of the world’s most renowned strength and conditioning coaches and as a result, they train world class athletes, college athletes, local high school athletes…and they also do small group training and one-on-one personal training for everyday athletes (also known as the ‘general population’).

This overlap of high performance athletic training and everyday training for, well, life is a breeding ground for excellent personal trainers. This is not to say that excellent personal trainers can’t be found at big box gyms. Quite the contrary. I just think that it’s from the more progressive strength and conditioning circles that comes the kind of quality education that distinguishes the best trainers and strength coaches out there.

What has bothered me for a long time is that there exists a mindset among some trainers—and trainees—that since the goal isn’t to make it to the Olympics, win a championship or become a professional, these sorts of high performance ideas and approaches to training don’t apply.

You don’t need to be training for the Olympics or trying to become a professional to apply high performance training principles and practices to your own growth and development as an athlete.

Movement Quality

A great example of the kind of thinking that has come from the collaboration of strength and conditioning and physical therapy is the Functional Movement Screen.

Put simply, the FMS is a ranking and grading system that documents movement patterns that are key to normal function. By screening these patterns, the FMS readily identifies functional limitations and asymmetries. These are issues that can reduce the effects of functional training and physical conditioning and distort body awareness.The FMS generates the Functional Movement Screen Score, which is used to target problems and track progress. This scoring system is directly linked to the most beneficial corrective exercises to restore mechanically sound movement patterns.Exercise professionals monitor the FMS score to track progress and to identify those exercises that will be most effective to restore proper movement and build strength in each individual.

http://www.functionalmovement.com/fms

The FMS uses a series of seven exercises to reveal movement pattern dysfunctions or limitations and asymmetries. This is important to know because it influences exercise choices. The screen lets me know ahead of time which movement patterns are safe to load and which require some remedial work before loading.

If a particular movement pattern is ‘dysfunctional’ then it shouldn’t be loaded because we know that’s just going to lead to an injury down the road unless that particular pattern is improved through corrective exercise.

For me, this is intimately connected to the first priority/responsibility of a trainer or strength coach which is to do no harm.

At the gym where I’ve been working, it is standard practice to perform a functional movement screen on every client before doing any sort of workout. For the movement pattern dysfunctions that are revealed in the screen, we prescribe corrective exercises.

Corrective exercise can be thought of as an umbrella term that describes the combination of exercises for improving mobility in the places that need to move better and stability in the places that need to be more stable, along with soft tissue work and, in some cases, exercises that teach proper motor control.

- This balance between mobility and stability is best described and understood through the lens of the joint-by-joint approach.

From this perspective, the challenge that trainers face is that clients want a workout. They want to feel like they’re working hard. Some even want an ‘ass-kicking’ (a trend I’m particularly uncomfortable with).

And for many people in the general population, their current movement capabilities make the popular exercise choices (bench press, barbell back squats, deadlifts, kettlebell swings) inappropriate. Conveniently for the trainers, there are still many, many options for exercises that will leave any client feeling like they got a good workout. It’s simply a matter of being smart with workout design.

Group Exercise

I think the reason that I chose to become a personal trainer and strength coach over being a group exercise instructor is that I’m too much of a technique stickler. Consequently, I have a great deal of difficulty with the format of group ex classes. Increasingly, it seems that group exercise classes want to be/need to be these fantastic, intense workouts where people get to do all sorts of cool exercises with cool equipment like the battle ropes, kettlebells and ViPR. There’s lots of sweating and burning muscles and soreness…all of the hallmarks of a “great workout”.

Many of these exercises require certain movement patterns to be minimally functional and actually require some fairly decent technique. In most group ex classes, there just doesn’t seem to be much in the way of technique coaching… let alone movement screening.

A good example is the hip hinge and the kettlebell swing. The hip hinge is essentially the touch-your-toes movement. It involves core stabilization and a weight-shift and it’s a movement pattern that a large number of people in the general population struggle with. You absolutely must have a good hip hinge (meaning you should be able to touch your toes) in order to perform a kettlebell deadlift.

Notice I didn’t jump straight to the swing?

Once the deadlift pattern is well-practiced and consistent at a reasonable lifting tempo, it then begins to make sense to add an explosive element to it. This is where we can begin teaching the KB swing.

The underlying skill progression concept at play here is that it’s important to practice good technique slowly at first to develop motor control. From there, we can begin to challenge the movement pattern by adding either or both of load and speed.

[That word right there—teaching—is why I struggle with the idea of group ex classes. There’s typically little to no room made for teaching.]

Please note: if an individual starts playing around with kettlebell swings—particularly if they’re heavy kettlebell swings (or deadlifts for that matter)—without having established a solid hip hinge pattern, then they are more likely to have compensatory motion in the lumbar spine. Excessive movement through the lumbar spine is also likely a product of limited core control.

This is a magical recipe for an injury. The good news is that it’s probably not going to result in a traumatic injury where something just all of a sudden snaps. I mean, it could—minor low back muscle strains are not uncommon. It’s also very possible that this dysfunctional pattern of loading is the kind of thing that your resilient and wonderful body will put up with. Until it doesn’t. This is where the repetitive mild trauma from overloading a movement pattern that’s not ready for it results

(And of course, I recognize that the idea of pre-screening participants for the sake of creating appropriate modifications is cumbersome and logistically over-the-top).

We’re all thinking it…

Speaking of intense, group-format workouts where intensity can often/regularly win out over good form, let’s talk about Crossfit. I think we could boil down the major criticism of Crossfit to being related to the use of the various Olympic lifts and exercises like the kipping pull-up.

Don’t even get me started on kipping handstand push-ups…

A crude oversimplification of Olympic lifting is that these exercises present the opportunity to lift a heavy weight from the ground to all the way overhead really quickly. They are lifts that can create a massive stimulus for strength gain…but they also come with a massive potential to cause injury. That’s not to say that the Olympic lifts are inherently dangerous. They are definitely highly technical and require a good deal of practice to get right. This is often thought of as the source of the problem: people just aren’t getting the technical coaching they need to do the lifts with good form.

I suspect the real reason that Crossfit and the Olympic lifts they do are associated with so many injuries is not just because people are not using good technique, but because for the majority of adults in the recreational athletic population, their ability to get both of their arms overhead is compromised. This whole sitting epidemic has resulted in widespread, sub-optimal overhead range of motion. Along with suboptimal mobility and stability.

For the majority of adults in the recreational athletic population, their ability to get both of their arms overhead is compromised

Restricted movement pattern plus load equals increased injury potential.

The same thing applies to the kipping pull-up. The movement itself isn’t necessarily inherently bad…it’s just that in most cases, people aren’t staying tight when they do it and they’re overhead range of motion is limited. This time the loading to their shoulders isn’t coming from above (compression), it’s coming from below (traction).

Floppy wet noodle body plus restricted overhead range of motion plus aggressive kipping pull-up motion definitely equals increased injury potential.

(You can tweet that if you like).

Getting to the point of this whole post

See where I’m going here?

It’s tricky, isn’t it?

I imagine/hope that at this point it’s clear where I’m going with this. My goal here is to start a conversation about how we take care of our athletes.

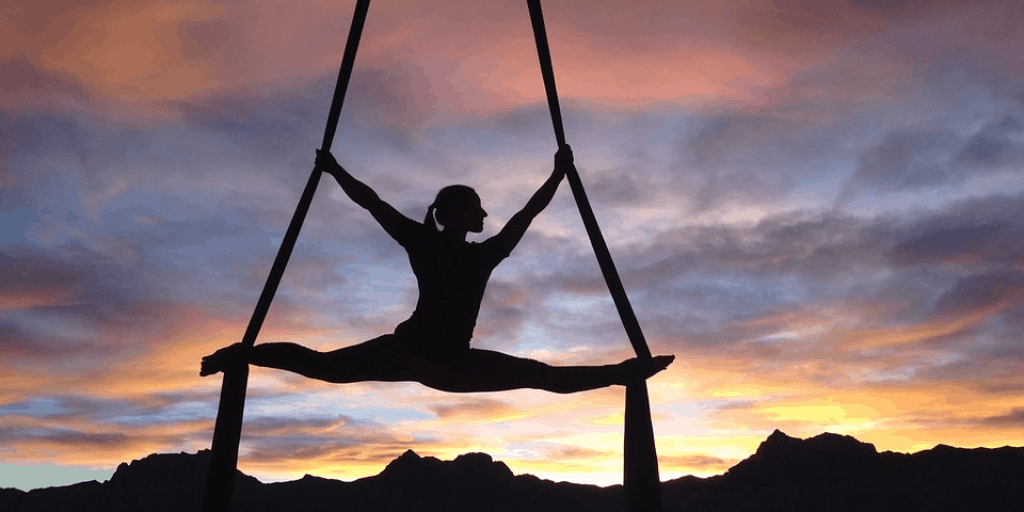

Circus arts—meaning trapeze (flying, swinging, duo, static, etc.), silks, rope, lyra, handbalancing, partner acrobatics, and any other discipline I’ve forgotten to mention—are physically demanding. Performing any of them generally requires a level of strength, conditioning, mobility and stability that can easily be described as exceptional…particularly when considered in the context of the general adult recreational athletic population.

We now know that loading dysfunctional/limited movement patterns can increase the risk of injury at some point down the road.

We can also be fairly certain that a large number of our students have restricted/compromised overhead range of motion. (Another fairly common limited movement pattern is the toe-touch/hip-hinge).

To be clear, when discussing functional overhead range of motion, it’s all relative: for many people, their lives do not require 180 degrees of overhead range of motion. Circus arts, however, tend to require that kind of range…so what counts as functional for non-overhead athletes is rather different than for overhead athletes (like circus athletes).

Tying together some of the ideas I’ve mentioned above, we have a scenario where people come to circus classes to learn the skills associated with a particular discipline. Sometimes there’s some conditioning at the end. Sometimes there are separate aerial/circus conditioning classes (I happen to teach one).

Knowing what we know now, the key question on my mind is what can we do to minimize the injury risks that circus athletes face resulting from movement limitations and/or asymmetries?

Having set the stage, I’ll outline some ideas next week.

In the meantime, I’d love to hear what people think in the comments below.

photo credit: Pixabay via Pablo.Buffer.com

Michael, I did not know/cannot believe you left TSNY. You were sooooo good for us students. I guess that shoulder problem must have changed your life. So sorry, but glad you have found a new career. Richard Huffman, TSNY, Washington, DX

Hi Richard! Thanks so much! TSNY and I actually parted ways in February. It was a difficult decision, but knowing they would be closing anyway it was time for the next chapter to begin. I’m planning to visit DC in the near future, so I’m sure I’ll see you around the rig.