Recently, a friend’s post sur les médias sociaux began an important conversation about quality coaching and quality movement. It started with an open letter, of sorts, from an aerial instructor to the aerial students of the world: if you’re performing skills or movements inefficiently, using the wrong muscles, then you can expect the result to be an inefficient movement/skill that may or may not look nice. Laura Witwer’s follow-up blog post adds that what you might really be doing is grooving that inefficient, probably not-so-nice looking, movement/skill into something more or less permanent. What follows is my contribution to the larger discussion.

First, I would like to say to Liza Rose from Fly Circus Space in New Orleans and to Laura Witwer: yes, yes, yes. A thousand times, yes! So well said. Thank you!

Fixing/undoing the permanent inefficient skill can be a rather long and annoying road. Especially when/if that inefficient skill/movement ends up becoming the cause of an overuse injury.

So the take-home point here is that you need to have a good coach there watching and coaching you to make sure that your form is solid and that you’re moving well.

You need someone there to remind you: “Squeeze your butt!”

But what if you can’t squeeze your butt?

What if, like sooo many circus artists, your glutes are, let’s say, under-active. (And, let’s get straight to it: under-strong).

We could call them sleepy glutes. Stuart McGill calls it “gluteal amnesia”. We could call it an acute case of weakness.

One way this breaks down could be like this: at some point in the relatively recent past, let’s say within the last ten years, you found yourself at a circus arts class. In one way or another, you fell in love with it. You took classes and classes and classes and here you are: you’re a circus artist-athlete.

Outside of circus, you need a job to pay for your circus habit. And at your job, you work at a desk. Outside of your job, when you’re not training, you might have a couch. Either way, sitting happens. And things happen to your body when you stay in one position for extended periods of time, over the course of days and weeks and months and years.

Unless you do some work to balance those effects out.

Put a pin in that idea, we’re going to come back to it.

So, while not everybody spends most of their days sitting at a desk, life does tend to involve a lot of sitting elsewhere. (And for the purposes of this post, let’s agree that many of us spend a fair bit of time sitting). I have gone on at length before about the potential impacts that sitting can have on your body, so here I’ll do a quick review:

Sitting—like any other thing we do regularly—is a form of training your body.

In the seated position, your hip flexors are shortened. Our bodies, with their wonderful capacity for adaptation, do their best to keep our hip flexors shortened.

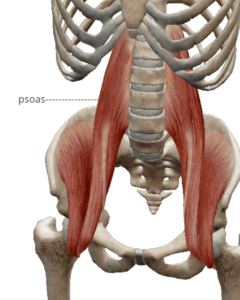

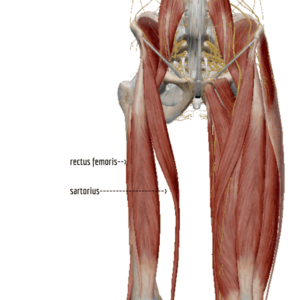

Your hip flexors anchor to the vertebrae of your lumbar spine and your diaphragm (psoas), the inside of your pelvis (iliacus) and the front of your pelvis (rectus femoris, TFL, satorius) and in their shortened state, they exert a bit of a downward pull on your pelvis, encouraging it to tilt anteriorly. Interestingly, this creates a bit of pull on your abdominal musculature. Combined with the way that sitting tends not to require much from your abdominal muscles, they can become “down-regulated” (kind of like switching to low-power mode).

This pelvic tilt also contributes to shortening and tightening the erectors of your low back…which reinforces that pelvic tilt in a fun chicken-and-egg kind of way.

And again, all of this combined with the way that sitting doesn’t ask much of your glutes means they also become “down-regulated”.

Nap time for your butt muscles.

Enter the Circus

So, your glutes are on vacation. And then you take up silks or trapeze or lyra or handbalancing or (insert active circus discipline here) and you start “training” to make your split bigger. In all of these, you find you need to move around in ways that, ideally, your glutes would facilitate.

To be explicitly clear, your glutes should be the primary drivers of hip extension pretty much any time hip extension happens.

Not only that, because of the way that your glute max goes from the midline of your pelvis (ilium) and anchor into the upper part of your thigh bone (femur), strong glutes help to keep the ball in the socket, so to speak. Your glutes add stability to your hip joint.

But what tends to happen is that people use their hamstrings to do the work:

Trying to do some “active flex” stuff to improve your split? Push down with those hamstrings!

Need to scissor your legs as you work on that hip-key? Hamstrings!

Working hard to arch up and lift your legs back in that croc? Hamstrings!

One thing that all of the above have in common is that your glutes should be doing more of the work than your hamstrings.

And, to be perfectly clear: this means your hamstrings end up working harder than they need to, which can definitely result in some freaking strong hamstrings, but it will also alter your hip joint mechanics and tends to result in hamstring strains and tendinopathies and such.

And…we haven’t even begun to touch on how, in the absence of full, active hip extension (which is what glutes are for!), the most common and insidious compensation happens through the lumbar spine! This is why core strength is so important: your lumbar spine doesn’t do well with loaded extension.

Now, admittedly, “loaded” is a tricky word to use here. The most obvious interpretation suggests that you might be extending through your low back with a weight in your hands or on your back. But the spine gets “loaded” in other ways:

(Notice his hips are not fully extended here. That means a good chunk of the “load” he’s carrying gets channeled into his low back.)

Without good alignment (here, we’re talking about hip extension to ‘neutral’ or ‘straight’), support from strong glutes and core, the forces get transmitted right into your low back. Over time, there’s a pretty good chance this could lead to disk degeneration. Reports suggest that is no fun at all.

That idea I said we’d come back to: It’s time to get those glutes working!

First we “activate” them…

(I’ve put activate in quotes because a muscle is never truly asleep. Down-regulated and not doing much, yes…but still alive, receiving neural input and capable of output. It’s just that the ‘output’ isn’t much of anything.)

…and then we acknowledge that “activating” them isn’t enough.

You’ve got to strengthen them.

We can get your glutes awake and feeling alive…but if your hamstrings are still stronger, we still have the potential for the same problems.

Hellooo glutes!

Add these to your warm-up/movement prep routine:

(if you’ve got a mini-band handy, I love these)

Banded Walks (or Banded Side-Steps to be more accurate)

Keys: this is intended to get your Glute Medius all fired up and ready to go…but it’s really easy for your hip flexors to try to ‘help out’ by doing most of the work, so form counts!

- Feet parallel (or even slightly turned in)

- Hips extended—turning the feet inward makes many folks flex at the hip (those pesky hip flexors again!), so think of your hips having headlights that need to be level and point forward.

- Keep tension in the band the whole time: step with one foot and then slowly move the trailing foot.

- No rocking side to side: I often tell people to pretend like they are videoing something important…we can’t have the shot tilting up and down with each step. That makes for poor videography.

- Do at least one set of 10 steps in both directions.

If you don’t have mini-bands…why don’t you have mini-band? They’re sooo great! [disclosure: that’s an affiliate link; the non-affiliate link is here.]

Side-lying Leg Lifts

- Again, form counts because it’s really easy for your hip flexors to jump in and do the work here.

- Lie on your side: hips stacked vertically (like really vertically, not just the ‘I think they’re vertical’ kind of vertical), shoulders stacked, head supported like you’re sleeping on your side

- Think Triple Extension: hip extends back, knee extends straight, ankle extends down (point your toes)

- Exhale and raise your leg as high as you can without letting it come forward (flexing at the hip)

- Do 5 repetitions on each side with a 5-second exhale on each.

Lumbar-locked Hip Lift (Also known as the Leg-lock Hip Lift or the Cook Hip Lift)

- Pull your current favorite knee in to your chest.

- The other foot is as close to your butt as you can do easily with your toes up in the air (so just your heel is pressing into the floor)

- Exhale, lift your hips and torso as a single unit and hold.

- Do 5 repetitions on each side with a 5-second exhale on each.

And then, it’s time to make those glutes stronger!

…except that “making your glutes stronger” is an ongoing process. Maybe what I should have said is “it’s time to start a weight-lifting habit!” because, let’s be clear: bodyweight exercises are not going to make you super strong.

[Note to self: write about the fallacy of bodyweight-only strength training.]

Why is that? Because, sure, in the beginning, when your glutes are weak, bodyweight exercises will feel challenging. And you will get stronger. But remember the principle of progressive resistance that is fundamentally key to getting stronger: unless you are steadily increasing your bodyweight (and thus, the resistance that your glutes have to overcome to do any given exercise), bodyweight exercises will not make you stronger.

(Phew. That feels good to get out.)

My glute (and other great posterior-chain muscle)-strength favorites of mine include:

- A staple in any program. (Follow the link for an introduction to deadlift technique). I like it as an introduction to the weighted hip-hinge that will lead us nicely into:

Single-leg “Straight-leg” Deadlift

The “straight-leg” part of the name is somewhat misleading. As much as it probably seems more circus-specific to do it with a straight leg, the slight knee-bend improves glute activation, and since that’s what we’re going for, bend your knee a little. It’s not cheating.

In terms of learning the movement, I suggest starting here:

And then, try this:

When you’re ready to load it, hold the weight in the hand opposite to your stance leg. Focus on keeping the back leg back by squeezing that glute like it’s your job.

Often, people get focused on tipping forward and this results in dropping the chest and rounding through the upper back. Not good. Options here include:

- focusing on lifting the back leg rather than tipping forward; the hip hinge will happen as a result; or

- focusing on lowering the weight toward the outside of your stance foot while keeping your chest up at the same time.

Of course, your strength-training plan wants to be as balanced as possible, but at least one deadlift variation should really be in there.

And then, voila! Four to six weeks later, when your coach says to squeeze your butt…BAM! You’ll be ready.

at my age of 82 I cannot do the single leg straight leg raise. any other exercise that I could do. Thank you

Hi Don,

I like to think of it this way: you just can’t do the exercise *yet*.

I’ve updated the post to include a suggested progression for learning the single-leg deadlift–so hopefully that will prove helpful. Additionally, you could try this two-legged version of the exercise: https://youtu.be/NAkFnyut3lI (there’s no need to use a particularly *heavy* weight–something easy to hold in your hands is a great place to start)

Let us know how it goes!

Pingback: Why Is One Side Of My Butt Sleepy? - Redefine Strength & Fitness

Pingback: Why Is One Side Of My Butt Sleepy? - Reimagym

Pingback: Why we do ‘agility’ ladder drills - Reimagym