Last weekend, Emily Scherb—Physical Therapist for Circus Artist-Athletes and Anatomy Nerd Extraordinaire—was in Boston. That fact alone was amazing for those already acquainted with her awesomeness, however she took it up a notch and presented a series of workshops. I had the good fortune to attend a pair of her workshops: The Acrobatic Spine and Hip: At the Core of Movement and The Shoulder: From Hanging to Handstands. Both were packed with great information and both have had me thinking about a number of things all week long.

What follows are my big takeaways from that afternoon of anatomical geekery, along with a couple of quotes from Shirley Sahrmann (just for Emily!).

The key to being circus strong is being able to effectively generate and transmit force through your core.

Emily came right out of the gate with what could be considered the mother of all concepts when it comes to athletic (circus) performance: the body’s marvelous ability to transmit and absorb force.

It sounds like the kind of thing that physicists or riggers might discuss. It’s definitely something biomechanics geeks discuss. It’s also a very important concept when it comes to injury prevention.

The riggers will appreciate this: a system’s ability to transmit or absorb force is heavily influenced by the path through which the force travels. In general, we’re looking for either straight or smoothly curved lines. Sharp angles, bends or narrow curves often mean that the amount of stress on a particular portion of the system is sharply increased.

For our purposes, the way you do circus stuff with your body is by generating force (or absorbing force) using one (or more) of your extremities and transmitting it into and through your core.

To do it well requires optimal joint positioning and movement mechanics as a foundation from which you can generate and absorb force.

This means that joint position and mechanics are kind of a big deal. If your shoulders or hips (or ankles) don’t move quite as well as they need to, force doesn’t move through those joints smoothly and that often means excess wear and tear.

And, at the core of this idea of force transmission is, well, your core.

[pullquote cite=”Shirley Sahrmann” type=”left”]During most activities, the primary role of the abdominal muscles is to provide isometric support and limit the degree of rotation of the trunk (lumbar spine).[/pullquote]

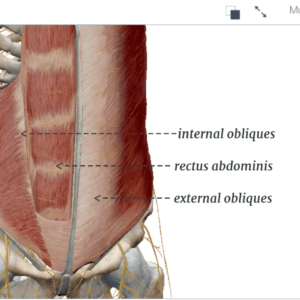

Your core musculature needs to not only be strong for circus, it also needs to be well-coordinated so that it’s engaged and active when it needs to be. I’ve mentioned this once or twice before: your core’s job is to protect your spine—primarily by stabilizing it and preventing unwanted (or unintentional) movement.

In circus, this is especially relevant when your spine is in positions other than ‘neutral’ (which happens a lot).

Speaking of your spine…

Spinal anatomy tells us a lot about how we should and should not move.

It was, for me, particularly helpful to have a vertebral anatomy refresher.

The shape of your vertebrae determines the type of movements they can perform best. And your vertebrae are shaped—and therefore interact with each other—differently in different portions of your spine. It is, in large part, these interactions that determine how they move.

The vertebrae of your thoracic spine, for example, are shaped in such a way that makes them better suited for rotation and lateral flexion (side-bending) by virtue of the way the individual vertebrae interlock with each other. Your thoracic spine isn’t the best with flexion and extension. (In fact, at best it has 10°- 15° of extension. That’s an incredibly useful and important bit of extension…but it ain’t much compared to what your lumbar spine can do).

Your lumbar spine, on the other hand, is great with flexion and extension.

This explains ideal backbend technique/position.

Copyright: fizkes / 123RF Stock Photo

So, about lumbar rotation…

Rotation is not something for which the lumbar vertebrae are particularly well-suited.

This reminded me of something Dr. Philip Beach wrote about the intervertebral discs of the lumbar spine, which is that “our lumbar IVDs (intervertebral discs) are particularly vulnerable to twisting insults”.

Listening to Emily describe the anatomy got me thinking about some of the movements you might see in a warm-up, such as the scorpion stretch.

As with any stretch, it’s worth taking some time to have a good think about why you’re doing it and what it is you’re looking to achieve. Just because your upper back feels tight and doesn’t feel like it can twist very well…and you feel less resistance when trying to twist your lower back…that doesn’t make it a good idea to try to make your lower back twist more.

The key becomes making sure that when performing twisting-type movements, the bulk of rotation should happen through the thoracic spine and that the lumbar spine is stable. As you know, I’m a fan of using strength training as a means of reinforcing and strengthening these sorts of important movement patterns. There are several exercises that regularly feature in my training plans that are intended to train and improve thoracic rotation with lumbar stability. Training this ‘in the gym’ means that when it comes time to move in your circus-discipline-of-choice, you’re much more likely to move well.

Rotation of the lumbar spine is more dangerous than beneficial and rotation of the pelvis and lower extremities to one side while the trunk remains stable or is rotated to the other side is particularly dangerous.

–Shirley Sahrmann

Circus artist-athletes are prone to overactive hip flexors

There are so many things in circus that require you to have incredibly strong hip flexors. In order for those strong hip flexors to be most useful, they need to have a stable anchor at one end. If you’re aiming to lift your legs (a straddle invert, for example), then your spine and pelvis need to be that stable anchor.

If your hip flexors are strong, your spine and pelvis need to be extra stable.

That, once again, is the job of your core.

All too often, the hip flexors end up stronger than the core and they overpower it at the initiation of movement. (Heck, sometimes you can see them overpowering the core when people are just standing there). What you’ll see is a bit of a ‘pop’ or ‘flare’ of the abdomen as the hip flexors tug the lumbar spine and pelvis forward when they first contract. The issue here is that it creates a momentary shear force on the discs in between the vertebrae and, over time, might not be the best for those discs.

The key, then, becomes training (deep) core activation prior to (or at the initiation of) movement. Ideally, this is unconscious, but sometimes things get out of sync. This is where people like Emily can be very helpful to know. This is also where it can be helpful to have this deliberately built into your strength training program (nudge, nudge, wink, wink).

Your core and your glutes work best when they work together

Training your glutes is something everyone should do—and for circus artist-athletes, that goes double. (See here and here.)

And, as alluded to above, core strength and control are vital for circus arts.

There is, however, an intimate relationship that exists between your core and your glutes. When we consider patterns such as lower crossed syndrome, it becomes easy to see how underactive glutes can have an impact on your core (and vice versa). In fact, there is a whole host of problems that can be avoided by making your glutes strong and making sure they’re working in concert with your core.

Strong lats: there is a time and a place

In order to move your arms overhead, your upper trapezius, lower trapezius and serratus anterior all work together to put your scapula where it needs to be.

Ideally.

A not-uncommon occurrence, however, is for the typical circus artist-athlete to develop big strong lats that end up overpowering the serratus anterior and lower traps. [Geekery alert:] I mean, after all, the fiber orientation of the lats is fairly similar to that of the lower trapezius…

The problem with having your lats doing too much work is that your lats do three things: shoulder extension, adduction and internal rotation.

To get your arms overhead, you need to do three things: shoulder flexion, abduction and external rotation.

You may have noticed that those are all opposites. This makes overactive lats less than ideal for getting your arms overhead.

This is where adding lower trap and serratus anterior activation and strengthening exercises important for circus folks. This is also one of several instances over the course of these two workshops where I felt glad that people smarter than me taught me to include those in my strength programming.

Force transmission and the importance of core control, making sure that your core and your glutes are working effectively and in concert with each other, along with making sure the muscles around your shoulder and hip are balanced and strong…

All of this brings me to this:

Whole-body, connected strength

Sometimes, you can fix a position or a movement flaw with different cueing.

For example, in your single-leg (or even double-leg) knee hang, engage your glutes so that you keep your hip extended (in neutral, really).

Or, in your hollow hang, make sure that your pelvic position (and thus, ‘hollow’ shape) is more a product of what your core musculature is doing rather than just having your hip flexors move your legs forward (all aimed at avoiding excess lumbar ‘arching’).

In both of the above cases, as long as the appropriate muscles are strong enough and you’re aware enough, you can make the appropriate changes. You’ll have to be conscious of this whenever you’re moving into and out of the relevant positions, and with practice, it will get better.

But if those muscles aren’t strong enough, you’ll always default to the pattern that has become your habit. This is where developing whole-body, connected strength comes into play. Strength training—done right—can be corrective; it can be balancing and it can be an opportunity to improve, practice and strengthen functional movement…not to mention minimizing your risk of injury.

I’m very grateful for having had another opportunity to listen to Emily speak about her passion for the intersection of physical therapy and circus performance and training. If you’re not already familiar with Emily’s work, please check her out here and here. She’s based in Seattle, so if you live nearby and your body feels like it could do with a bit of care, here’s where to go. Actually, it might even be a good idea to pay her a visit if you’re just looking to improve how your body performs.

[mc4wp_form id=”623″]

Pingback: Dear Trainees… | Get Circus Strong

She’s doing the Shoulders: Hanging to Handstands workshop in Vancouver this weekend at West Coast Flying Trapeze, should any reader be nearby! https://www.facebook.com/events/1924870761132589/