[alert type=”info” close=”false”] In case you missed it, you can find part one here. [/alert]

Functional movement represents the basic foundation for long-term health and performance in any athletic endeavor (and, I would like to suggest that living as a human counts as an athletic endeavor).

It is also a term that is wildly misused and misunderstood and has become tragically buzz-wordy in the fitness world.

[I can see room for a tangent on the differences between the fitness world and the strength and conditioning world. But that’s for another time.]

First, let’s talk movement dysfunction.

In order to make sense of functional movement, I’d like to begin by illustrating the other end of the spectrum: not-so-functional.

In general, the most common—and easy to spot—dysfunctions we’ll see in people are known as:

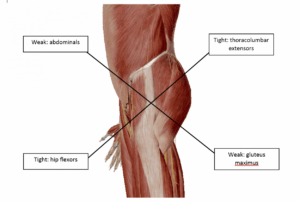

Both represent patterns of muscles that have become over-active and tight alternating with muscles that have become under-active and weak. It’s possible that one causes the other.

Two very common examples of movement restrictions that result from each of these are overhead (shoulder) range of motion limitations and squatting (functional hip range of motion) limitations.

Lacking overhead range of motion?

What you’ll see are compensations through the cervical spine (that forward head position that reminds me of a turtle sticking its head out of the shell…say no to the turtle!) and lumbar spine (rib flare and arching; sometimes obvious, sometimes subtle, both not so good).

Both of these, over time, put strain on structures that just don’t need the strain. You know, like the intervertebral discs of your spine and/or your labrum.

Can’t squat?

This is where you’ll see rounding of the lumbar spine, probably some forward head posture (say no to the turtle!) and a ‘butt wink’ (a rounding under of the pelvis that looks like the butt winking at you…but not in a sexy way). Again, this means the strain gets translated into the spine…

If you’re looking closely, you’ll probably also see one or both ankles with limitations as well.

If you (or someone like you) can’t dissociate movement of your femurs from movement of your pelvis and lumbar spine when you’re standing on the ground, it means your lumbar spine moves more—and strains more—than it should.

It’s also worth questioning: if you (or someone like you) can’t stabilize through the hips when standing on the ground, how well is that going to go when you try to do it in the air?

This is a brief tangent: Things I’ll probably say more than once

The thing is, you don’t have to have full overhead range of motion to do circus. Nor do you need to be able to squat. (And those are just two examples of functional movement). You can train for aerials or do handstands and probably never have any pain.

Probably.

Because your body can handle it.

You know, until it doesn’t.

The trick of it is that inadequate mobility (or stability, for that matter) when combined with rigorous training is a bit like driving your car for miles and miles with poor alignment. Things will wear unevenly and might eventually breakdown. But here and now, if the car isn’t making any noise, why would you think to get it fixed? Why worry about a future problem?

Getting back…

Most often, soft tissue injuries are the result of forces that exceed tissue capacity.

I want what that statement means to be crystal clear, so just in case it’s not obvious, I’m going to elaborate and clarify:

In the majority of cases, when someone experiences a soft-tissue injury (which means an injury to muscle, ligament or tendon), it happens because of a force acting on the muscle, ligament or tendon that exceeded the amount or type of force that tissue was capable of handling. Another way to put it could very well be to say the tissue was too weak to handle the load.

In some cases, this isn’t just a matter of making the injured muscle/ligament/tendon stronger. A great example is a hamstring strain. We could probably avoid a lot of hamstring injuries if we did more glute work. When the glutes aren’t active enough, the hamstrings often jump in to action to compensate. This results in hamstrings trying to do work they’re not really meant to be doing.

Over-worked hamstrings eventually break down.

In other cases, it really is a matter of needing to make the muscles stronger. However, we can’t just dive into strength training without making sure the movements we’ll be strengthening are functional.

Basic functional movement is the prerequisite for effectively building tissue capacity and mitigating injury risk.

Knowing this, what can we do?

The norm right now is for us to wait for dysfunctional movement patterns to lead to an injury…and then we send them to PT.

But this isn’t because instructors are just ignoring obvious problems…it’s because many instructors don’t know what to look for and/or don’t have the appropriate resources/knowledge/skills for addressing the issues before they become problems.

Don’t get me wrong: referring a student to an orthopedic surgeon or a physical therapist when they are in pain is the single best move you can make.

When they are in pain.

There is, however, an alternative: we could aim for legitimate prevention…

“All the biomechanical techniques in the world, render themselves useless, in the absence of physical readiness.”

– Gerald S. George, Ph.D.

Sidebar: we have largely misunderstood prevention up to this point.

A common example of how we, the circus community, have misunderstood injury prevention is the common refrain ‘I’ve gotta keep doing my PT exercises…’

Now, don’t get me wrong, those PT exercises are very helpful. The problem is that they were never meant to be the entirety of the solution.

Let’s take the example of an aerialist who was in physical therapy for impingement pain, which was ultimately a result of their lower traps being underactive and/or weak.

The PT helps their irritated muscle to heal and teaches them a set of exercises designed to enhance mid and lower trapezius functioning and improve the overall movement of their scapulae (with a focus on upward rotation with shoulder flexion).

The aerialist takes these exercises and does them before every training session…

which is great…but…

What would be really great is if the aerialist had a strength training regimen that used these exercises as a primer for building strength with the newly improved muscle function and joint mechanics.

What would be even better is if their strength training plan included not only strength work for that particular movement pattern, but also exercises that develop balanced whole-body strength.

This is where functional movement and corrective exercise come into play.

So what is functional movement anyway?

Just so that we’re clear: I am not talking about primal movement or any sort of animal flow-type thing here. These sorts of things have the potential to be great…but for many humans out there, we’re more likely to end up moving poorly or creating/aggravating an injury because their bodies just are not ready for this kind of exercise.

“Functional” depends on context.

[Again, functional is also a widely misused and misunderstood term…but we’ll use it for now and come back to this particular point another time…]

The foundation of all functional movement is having a balance of the joint mobility and stability required to express the following basic human movement patterns with integrity:

- Squat

- Hip Hinge

- Step

- Lunge

- Horizontal Push and Pull

- Vertical Push and Pull

Functional movement simplified

Let’s dig deeper: what does it mean to have the “balance of the joint mobility and stability required to express [those] basic human movement patterns…”

It means, can you (or someone you know) dissociate (move independently of each other):

- Scapula and Cervical Spine?

- GH Joint and Lumbar Spine?

- Femur and Pelvis?

- Femur and Lumbar Spine?

…and do it “with integrity”?

This could really be oversimplifying (except it’s not, really) but one particularly powerful indicator of whether someone (like you?) can perform a movement with integrity or not is whether they (you) can breathe normally as they move.

In particular, can they (you) breathe normally (while maintaining form) at end-range?

Or when performing the movement under load (again, while maintaining form)?

“Essential to the concept of functional training is learning to move before you load.”

–Mike Boyle, New Functional Training for Sports, 2nd Edition.

Corrective Exercise

…is most often associated with rehab, but actually represents a strategy for strength training that works on improving dysfunctional movement patterns while building strength.

In its most basic form, a corrective exercise strategy is meant to reduce stiffness in overactive muscles, activate or strengthen underactive muscles (building good stiffness), and re-train the nervous system to integrate the new joint positions or muscle patterns into daily movement use.

Corrective exercise is not meant to stand alone.

Gray Cook’s metaphor is that doing corrective exercise is like editing a Word document. Using the (temporarily) improved pattern under load (strength training) is how you hit <save> on your document.

Attempting to strengthen a faulty movement pattern is just making the dysfunctional pattern stronger. Kind of like having the alignment off on your car and deciding to drive farther and faster.

Doing corrective-type exercises without then doing some strength training is like editing the document and then closing the file without saving.

Bottom line: to improve movement quality, we need both exercises to improve it (I’d actually prefer to avoid saying we’re correcting movement) and exercises to train the improved movement patterns under tension (which really means with some appreciable resistance).

The Performance Continuum

- The Performance Continuum

In many sports, particularly at the higher levels, there exists a continuum of care, so to speak. At one end, we have an athlete’s entry point: the sports medicine team. They are the ones who perform the initial assessments and screens.

From there, they hand the athlete off to the strength and conditioning team and the skills coaches.

The strength and conditioning team’s job is to build the athletes capacity (make them stronger and build conditioning to make them more resilient and capable of more skills training). It’s worth noting that strength and conditioning coaches often do screens and assessments of their own—so they can see what the PTs described to them. A second set of eyes is always helpful.

And then we have the skills coaches, who teach and develop the skills the athlete’s need in order to perform well.

I think you might be able to see where I’m going with this—and since this post was way longer than part one, I’m going to pause here. Next week, I’m going to discuss how to build balance strength for long-term, healthy circus participation. And, most importantly, next week’s post will be where we begin discussing some ideas on how to improve our overall culture of safety and injury-prevention.

Pingback: Hey bendy people! Managing hypermobility for circus (part two) | Get Circus Strong