For some of you, this may be difficult to hear. I know you like this one and it probably feels satisfyingly good…it’s just that it probably isn’t stretching what you think it’s stretching.

For some of you, what I’m about to suggest will mean an apparent slowing of the pace of your progress. In the long run however, your body will likely be happier for it.

I’m talking about a certain ‘hip flexor stretch’ that we all know and many people love. It’s not uncommon for even the more flexible folks out there to feel like their hip flexors are tight.

It looks a little something like this:

But we love that stretch!

It’s about your hips, you see.

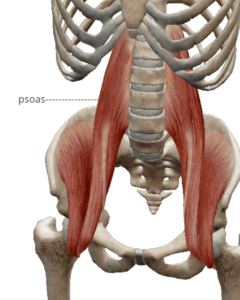

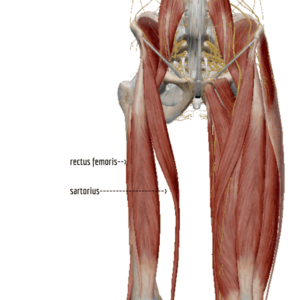

Allow me to explain with a brief review of the anatomy of the hip joint.

Like your shoulder, your hip is a ball and socket joint: the head of your femur (thigh bone) is the ‘ball’ and the acetabulum of your pelvis is the ‘socket’. Like your shoulder, the socket is deepened by a fibrocartilage labrum.

The hip is generally more stable than the shoulder joint though. Like the shoulder, there are passive constraints—structures that provide some inherent stability to the joint. In addition to the bit of stability that the labrum adds to the picture, on the front of the hip joint, we have the iliofemoral ligament and the hip joint capsule.

When you extend your hip—walking, running, stretching your split—the head of your femur wants to translate forward (essentially out of the socket) and these structures prevent it from moving too far.

Next we have your hip flexors.

Here’s the problem

When you do this particular “hip flexor” stretch, it creates additional lumbar lordosis (arch in your lower back) and anterior pelvic tilt (meaning your pelvis tips forward). Conveniently, we can use the top of her tights as an indication of how her pelvis is tilted forward.

What this does is take tension out of your hip flexor muscles (the arching of the lower back and the tipping of the pelvis forward moves the origins of each of your hip flexors closer to their respective insertions) and places all of the stress on the passive constraints of your anterior hip

Over time, stretching these creates microinstability in your hip, which basically means the femoral head is sliding around to a slight degree inside…and a little outside…of the socket.

Your body is an incredible thing: it notices this instability and, in the spirit of being helpful, your hip flexors will tighten in order to make up for the lost stability.

What follows is the circus artist/athlete thinking ‘Oh, my hip flexors feel tight!’ and then they stretch some more.

Since the aforementioned stretch tends to involve stretching the aforementioned problems, ligaments get stretched, hip flexors reactively shorten and the circus artist/athlete says ‘My hip flexors feel so tight!’

Stretching follows and the cycle repeats itself.

The real problem is that this hip instability thing can result in additional stress on the labrum and eventually lead to tears (and/or other uncomfortable complications).

Nobody likes a labrum tear.

What to do?

First, here’s a better way to do this stretch:

- Position your knee directly under your hip. No further back than that. Seriously.

- Squeeze your glute on the down-side leg.

- Tall posture. Place your hands on your lead knee and press down. This should help you activate/brace your core.

For those who don’t feel a stretch here, that might be ok at this stage. I’m showing the starting position for this stretch. If you’re working toward a split, chances are you’ll have greater hip extension than I’m showing here.

The most important things to remember with progressing this stretch are:

- Always keep your glutes squeezed. Because of the way your glutes attach to your femur, squeezing them helps to keep the femoral head from translating forward and straining the passive contraints (and making the hip flexors think they need to do extra work).

- Keep your core engaged. This will help minimize the arching in your lower back.

Make sure you’re doing those two things every time you stretch your split, and you’re more likely to keep your hip happy in the long run.

For some people out there, you may be in deep. You’ve been stretching this way for a while and backing off is going to be hard. It may take some time for your hip flexors to get the message and settle down. Really, if your hip flexors are feeling tight all the time or your hip is feeling aggravated, I would suggest visiting your friendly neighborhood circus- or gymnastics-savvy physical therapist to get it assessed.

Train smart. Get strong. Get circus strong.

PS. This post is inspired by a similar post from Dave Tilley, which you can find here.

After many years of doing aerial silks and lyra, I stopped being able to touch my toes (after years of being able to do so easily.) A physical therapist diagnosed me with a rotated pelvis (caused by hip instability). My PT told me it was likely caused by years of doing a desk job, but after reading this post, I am wondering whether it may have been the desk job combined with years of doing this particular stretch incorrectly. After a year of mobilizations and exercises, my hips are still very unstable, and my PT says that this may be an issue of managing rather than solving. I would love to hear your thoughts on further exercises to help stabilize.

Hi Aurelia,

I’m sorry to hear about your hip! It sounds like you’ve found a good PT to help you manage the situation. It’s hard for me to comment about your specific case because there are too many variables I don’t know. Where I would begin is to have a discussion with your PT about the exercises they’ve given you and where to go with them from here. After the more advanced phases of rehabilitation, there’s room to move into strength and conditioning. The key, of course, is to progress sensitively. The point being to take the gains you’ve made in PT and build upon them. I realize this is an incredibly general response, but this is a great example of how programming/exercise prescription should be tailored to the individual. The best thing to do would be to find a great strength coach who is willing and able to communicate with your PT so that they can build a strength training program *for you and your body*. The trick is making sure the strength coach understands movement and what you want to be able to do.

If it’s that bad, you should look into prolotherapy and/or PRP.

It can help tighten ligaments. Worked wonders for me.

But how do you then approach things like parallell front splits or the firebird leap?

So essentially don’t stop doing this stretch…Just do it properly? I run into this same issue with my kids (dancers) when we are stretching in a lunge. I always tell them it isn’t an ab/back stretch because many of them think they should lean into the arch. My guess is this started from gymnastics/acro…but either way, you could use a “how it should feel approach”. The minute I tell kids to engage their core and explain where they should feel the stretch, they quickly understand how to correct it. This article is a great way to explain how to do the hip flexor stretch correctly, which in actuality the last photo is probably where the majority of humans would be once they refocus the intent of the stretch and engage the core/alignment. However, the headline of stop doing this stretch is a bit of a “stretch”. As your article shows, people can be educated and are capable of correction. Realistically, if done properly, nothing is wrong with this stretch.

So what’s the progression for more flexible people ?

Yes please explain the progression for people already in flat splits thx

I am curious as well!

Pingback: Aerialibrium - 5 Questions to Ask Yourself About Your Hips

Pingback: Aerialibrium - 4 Stretches You Potentially Have Misaligned

Pingback: Strength Training for Circus: 3 reasons to add weight-training to your circus training (part one) | Get Circus Strong

Pingback: 4 Stretches You May Have Misaligned – Redefine Strength & Fitness

Pingback: 5 Questions to Ask Yourself About Your Hips - Reimagym