In that same presentation where Coach Boyle reminded us of the useful practice of stealing smart people’s stuff to use with our own trainees—the topic was conditioning (not to be confused with strength training)—he also posed the question:

What if the way we’ve always done things is wrong?

What if the way we’ve always done things is wrong?

Now there’s a fun thought exercise.

I should point out that I’m not suggesting that the way you or someone like you warms-up for your circus fun time is wrong. I am going to say that I enjoy questioning the status quo…especially when the status quo doesn’t seem to have been questioned lately.

So here we are, having established a general idea of how relative stiffness can influence movement. Specifically, we’ve looked at overhead shoulder flexion and hip hyperextension—two movements that have broad and significant applications in circus (‘cause they’re everywhere).

But here’s a place where we often get tripped up: using these two examples, we know the movements, but do we know the movers?

Allow me to elaborate…

Since we’re talking about the idea of the more general, group warm-up, let’s start here. When planning the warm-up, I think it’s important for us to start by asking ‘Who are we warming up?’ followed by ‘What are we warming up for?’

Who is warming up?

A reality that we need to appreciate is that a large number of the folks who come to circus classes—of all levels—have likely spent their day at their desk. Sure, some folks have standing desks (but standing all day isn’t necessarily better than sitting all day) and maybe even some of them are consistently varying their position from seated to standing throughout the day (and to those folks I say, well done!) …but odds are, many of them have been in pretty much one position all day long.

For their upper bodies, that means:

Their upper traps, levator scapulae and suboccipitals (muscles on the back of the neck-ish) are likely facilitated: they’ve been ‘on’ all day long, supporting the head and that means they’ve got a bunch of extra tone (tension).

Their deep cervical flexors have been told they can have the day off: they’re inhibited and very much lacking in good stiffness. (Possibly any stiffness).

Their pectoral muscles (major and minor) have also spent the day in a shortened position. They’re also facilitated and have too much stiffness (because they’ve spent the day effectively training to be short and stiff).

Their lower traps (their lovely, wonderful, useful lower traps!) and rhomboids are also likely inhibited and not really ready to do much. Actually, it’s not uncommon for our good friend, serratus anterior, to also find itself in a somewhat shortened and inhibited situation as well.

Oh hey…funny story about the upper traps, lower traps and serratus

Oh hey…funny story about the upper traps, lower traps and serratus: together, they form a force couple. It’s funny because it’s called a force “couple” but there’s three muscles. Ahh…that always makes me chuckle…

But anyway, these three muscles all play an important role in facilitating the scapular upward rotation (and elevation and posterior tilt) required for full overhead shoulder flexion.

I’m sure that the large role that overhead shoulder flexion plays in circus combined with the underactive lower traps and serratus anterior makes for a pretty obvious issue that we would do well not to ignore.

And then, there’s their lower bodies:

I’m going to start with the glutes.

I’m actually pretty sure that I cannot understate how important—and under-trained—glutes are…for humans, in general, and for human circus artists, in particular.

All too many folks don’t train their glutes nearly as intensely as they need to and the amount of time that we all (or a large majority of us, anyway) spend sitting does not help the situation.

That means that for many of the folks coming to circus classes, their glutes are inhibited (and probably a bit weak, as well).

[alert type=”info” close=”false”] A brief moment to explain the distinction:

When a muscle is inhibited, the relative lack of use of that muscle has sent a signal to the nervous system saying we don’t use this muscle much. Consequently, the neural input to the muscle gets downregulated or suppressed. Basically, it ceases to become a quick-to-access muscle. (Please note: the muscle still works…just not quickly or effectively).

One of the things we need for circus is for the muscles we need to be quick-to-access. In the absence of glutes that are ready and raring to go, other muscles will compensate. Like the hamstrings, for example. But nobody ever over-worked their hamstrings in circus, right?

Facilitated muscles, on the other hand, are like the kid in class who always shouts Pick me! Pick me! Pick me! I’ll do it! I’ll do it! I’ll do it! Even if it’s not the best choice for the job, facilitated muscles typically end up being upregulated in terms of neural input because they are compensating for other muscles.

Why are they compensating?

…this brings us to weakness. A part of me would prefer not to use the term weak because it carries some baggage with it. However, it remains a good one-word equivalent of not-strong. And that’s an important consideration: muscles don’t just get strong on their own. You can have glutes that are really awake and alive and ready to go…but if you’re not training them, they’re not going to get stronger. (And chances are they’re not as strong as they need to be).

For more, please refer to my thoughts on deadlifts. [/alert]

Getting back on track…

It is increasingly popular (meaning common) these days for people who sit at their jobs or who sit at home when relaxing after a day at their jobs (or folks who simply engage in sitting for more than twenty minutes at a time) to have—not only sleepy glutes—but also…

…hip flexors that are short and tight and facilitated. Too much stiffness when compared to their abdominals…

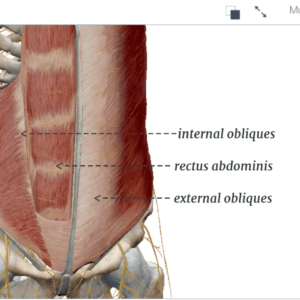

…which are likely underactive and probably even a bit short.

Gasp! Underactive abdominals?

(“Fun” anecdotal observation: lots of circus artist-athletes have hip flexors that end up doing a lot of the work that their core should be doing).

Continuing the vicious circle, facilitated hip flexors and inhibited abdominals often also mean…

…back extensors that are short and tight. This means too much stiffness when compared to their…

…which—and I may have mentioned this once already—are all too often inhibited and underactive and understrong.

And, as if I haven’t painted quite a picture already…

On top of all that, folks are coming to circus training carrying in their bodies whatever stresses came with their day (or week). What this often means is additional neurological muscle tone. Read: they’re carrying extra muscle tension that they don’t really need. And it’s probably in all of the places where we don’t really need it.

So… what to do?

Well, acknowledging that what I’m about to present represents a departure from what seems to be the norm for warming up, here goes:

My preference is not to begin with running or jumping. As I said, folks are coming in with higher levels of sympathetic tone than they need for optimal performance and I would really much rather fine-tune some relative stiffness before asking them to execute any particularly dynamic movement patterns.

Breathing

So if I’m being really honest, my favorite place to begin is with a breathing exercise in order to create a parasympathetic shift. [Jen Crane has written about this recently and she has a very good summary of how your sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of your autonomic nervous system work here] I have written about this before as well and maybe having your whole class or group of classes start by lying down on the floor isn’t for you. Another similarly effective option would be to do some breathing in a kneeling position.

It’s not the most exciting video to watch, but here are the key points:

- Sit comfortably and upright.

- Allow your chest to drop just a little bit. It’s ok. It’s just a mini-slouch.

- Place your hands on the front of your ribs.

- Inhale through your nose.

- Exhale through pursed lips and let your ribs drop.

- Now, as you inhale through your nose, try to keep the front of your ribs in place as your lungs expand laterally and posteriorly. That’s right: inhale out to the side and into your back.

- Exhale and “stitch” your ribs together just a little bit more.

- Repeat for 5 breaths.

- That’s right: just five breaths. It takes about 45 seconds or less to do…and it creates a bit of a parasympathetic shift, encouraging your body to let go of some excess tension.

This sets you up wonderfully for what would be my second favorite thing to do next:

[alert type=”info” close=”false”]

Just for the sake of having a quick review handy:

What we want:

- Core stiffness

- Glute stiffness

- Scapular stabilizer/upward rotator stiffness

It’s rather simple, actually. The trick here is that stiffness of these tissues comes from your strength training (assuming you do that) and in the warm-up, the best we can do is prime the stiffness that’s already there.

What we want to modulate:

- Lat stiffness

- Spinal erector stiffness

- Hip flexor stiffness

- General, excess sympathetic tone.

[/alert]

Foam rolling.

I should say here that I completely understand that in many situations, there are logistical considerations that make this completely unrealistic. I get that. All the same, here’s why foam rolling right after breathing and before you start moving is a great idea:

- It continues to assist in decreasing sympathetic tone.

- It assists with hydrating muscles.

- It provides a pre-exercise check-in with your body: a quick, full-body routine can be done in about eight minutes. Five, if you’re super-disciplined. And by rolling each major muscle group, you get to see just how everything is feeling today. The ongoing improvement in self-awareness is invaluable.

This isn’t the place for me to do a write-up on how to foam roll, but there are some good ones here, and here. And if you really want to go down a rabbit hole, check out Dr. Andreo Spina’s video.

Now then, since we’re already on the ground, this provides a great opportunity to begin reinforcing good stiffness:

Leg Lowers

Why?

- These reinforce not only core stiffness, but active hamstring flexibility (mobility!) and contralateral lumbopelvic control and dissociation.

- There’s a lot of room to get excited over “active hamstring flexibility” in our “stretch it if it feels tight” world, but the hamstrings are a great example of muscles that can seem “tight” and lead us to want to stretch them when “tight hamstrings” are very often in need of something other than stretching. Good core stiffness can go a long way to remedying this without ever needing to stretch. But I digress…

How?

- On your back, exhale fully as you raise both legs as high as you can. Obviously, for some, having a band or strap to hold one leg would be beneficial. If you have room to individualize, by all means, do.

- Note: your lower back does not have to be flat against the floor. Some arch is good.

- Take a breath in through the nose. Exhale fully as you lower one leg with control.

- This is circus, so straight knees matter. (They matter even outside of circus).

- Only lower your leg as far as you can without changing the arch of your low back. This is core control.

Floor Slides

Why?

- Adding stiffness to external rotators and scapular retractors.

- Lengthening internal rotators (and encouraging a decrease in unnecessary stiffness)

- And, if you cue the exhale with the upward (concentric) movement (which I cannot recommend strongly enough that you do), we continue practicing deep core engagement…and, most notably, it’s overhead reaching with deep core engagement (and, ideally, optimal ribcage positioning). I don’t know if I can emphasize enough just how important it is to groove core engagement with overhead motion.

How?

- On your back, start with your arms in the 90/90 position.

- Take a breath in through your nose and press your forearms into the floor.

- As you exhale (fully), continue pressing your forearms into the floor as you slide your arms ‘up’ and extend your elbows.

Single-leg Hip Bridge

Why?

- I think that I may have mentioned glutes already, but here is your opportunity to send a message to the glutes that hip extension is their job.

- Again, cue a full and forceful exhale through pursed lips (like blowing out the candles on a birthday cake attached to the ceiling) and you link deep core muscular activation with hip extension.

- Pulling the one leg in restricts lumbar spine extension (the most popular way to compensate when your glutes don’t do hip extension very well) and creates an anti-rotation stimulus. Don’t be surprised if actively extending your hip without any lumbar extension is hard.

How?

- Pull one knee into your chest. Lift the toes of the down foot so that only your heel is in contact with the floor.

- Inhale through the nose. Exhale fully as you drive through the heel to lift the hips–and hold until you run out of breath.

- Lower, inhale and repeat.

Dead Bugs

Why?

- I love Dead Bugs and think that everyone should do them.

- The main purpose of the Dead Bug is to train core stability (and let’s be clear: by core stability, I mean the ability to keep your spine from arching or flattening) in the presence of shoulder flexion and/or hip extension.

- The key to being able to do this—move into full shoulder flexion or fully extend the hip—without allowing the spine to move is that the stiffness in your anterior core must be greater than the stiffness in the muscles opposing shoulder flexion (your lats and pecs, for example) and hip extension (your hip flexors mainly).

- As I’ve mentioned already, we’re not going to develop stiffness in the warm-up, be we can reinforce the stiffness that’s already there. With time and repetition, we can begin to shift things…but that’s drifting into a thought on strength training and this is a thought about warming up.

How?

- On your back…again, you don’t have to have your back flat against the floor.

- Inhale through your nose. Exhale forcefully through your mouth and raise your arms and knees up toward the ceiling/sky (if you happen to be outdoors).

- Inhale through your nose. As you exhale (fully–remember, we’re blowing out candles on the ceiling), bring one arm down towards the floor while the opposite side hip/leg extends. Again, only lower the leg as far as you can without losing core/spine position.

- Inhale to return. Exhale and repeat for the other side.

Bear crawls Strict Bird-Dog

Why?

- The real beauty of the quadruped position is that it provides a fantastic opportunity to practice controlling the movement of your spine while extending your hips and/or flexing your shoulders.

- This is also a fantastic way to prep your rotator cuff and scapular upward rotators.

- Start by doing a Bird-Dog—kind of like crawling in place—and get the same benefits you would get from doing some version of a Bear Crawl (and this might be the most prudent way to go since the Bear Crawl is an exercise that loses all value if you can’t keep your torso still when you’re doing it).

- Add a full exhale through the mouth to reinforce the core activation and you get a lot of bang for your buck.

How?

- Start in quadruped. Set yourself up in a neutral spinal position. No tucking and not too much arching. Neutral.

- Inhale through the nose.

- As you exhale, slowly slide one hand and the opposite-side foot (toes) along the floor until your finger-tips and toes just come off the floor. Remember: full exhale.

- Inhale as you return to the start position. Exhale and switch sides.

Do each of these slowly and with a full exhale on each rep. The exhale should be audible. (Get your friends involved, it’ll be like a symphony of exhales!) I tend to suggest between five and eight reps per exercise.

So there you go. Give these a try as a part of your warm-up and see if your body feels the difference.

The preceding is by no means a complete warm-up. I just wanted to provide a short list of a few must-haves for your movement prep. The reason why these exercises are on my must-do list is that they each help us to reduce bad/unwanted stiffness while encouraging good stiffness. Because some of them contain elements requiring cross-body coordination (e.g., left arm-right leg move at the same time), they serve a dual purpose by warming up your brain-to-muscle connections as well.

Obviously, after these you could add some more moving around—walking, skipping, running—to get the heart pumping a bit more. I could go on about other elements of the warm-up as well, but for now, I’ll stop here.

Thanks for reading!