We (meaning me; I) interrupt our regularly scheduled programming for a rant.

Wait, it might not be a rant.

(Actually, it might be…I’m either going to rant or ramble. I can’t quite tell just yet.)

I frequently find myself in conversations with other trainers and coaches, nerding out about what we do. Often times, I like to start those conversations because I regularly have something training and performance-related on my mind that I would like to discuss with a colleague. And other times, I am not the one beginning the conversation. One such example occurred recently.

The topic of functional training came up. My personal trainer colleague casually said, I don’t like functional training because what’s functional for one person might not be the same as what’s functional for another person. And that’s when it got interesting because, well, yes and no.

(Before I go on, I would like to clarify: this is not an attack on the individual in question. I don’t know them particularly well, but I respect them. We had a great discussion and it really got me thinking about what follows because this particular topic/idea…or, shall I say, misconception, is probably resulting in/going to result in people being more likely to get injured, rather than less likely—which is actually supposed to be the point. Allow me to explain.)

On the one hand, that particular statement serves as a reminder of the importance of individualizing training plans. Different people have different bodies, their alignment will be different and consequently, their movement patterns and muscular balance/imbalance will also be different.

And the only way to truly individualize training is to assess the athlete.

And, on the other hand, statements like that (“what’s functional for one person might not be the same as what’s functional for another person”) kind of drive me a little bonkers.

Maybe a lot bonkers.

Let’s talk history for a moment!

It probably all began in the 1990s when physical therapist Gary Gray, introduced a new way of thinking about muscle function. In place of the old-school view of anatomy—where a muscle’s function is thought of in terms of its origin and insertion and how a muscle contraction might move an isolated joint—Gray got us thinking in terms of kinetic chains and functional anatomy—where muscles act to move (or resist movement of) interrelated groups of muscles and joints.

Then, in 1997, Gray Cook, Lee Burton and a few others created the Functional Movement Screen. About ten years later, Mike Boyle and Gray Cook had a conversation that lead to the joint-by-joint approach to training. The idea of building training programs based on movements not muscles caught on.

Sort of.

In certain progressive corners of the industry.

To be honest, this represents the fundamental difference between how a bodybuilder trains and how an athlete should train to improve performance.

Reminder: circus artists are athletes.

So… those good old fashioned bodybuilding training splits still happen: back and bis, chest and tris, legs and abs.

Even with non-bodybuilders.

And as with many new and/or revolutionary ideas, there were (and still are) those who ‘got it’ and those who were (and still are) just excited about riding the wave.

Functional movement gave way to functional training.

And somewhere along the way (of course), functional has gotten a bit buzzwordy and I think we’ve lost track of what it means.

This is where that particular aspect of the fitness industry drives me a bit bonkers.

Let’s be clear: I am by no means an expert, nor am I under the misguided impression that I know anything close to everything on this topic. Nevertheless, I would like to offer the following clarification.

Just what is functional anyway?

If something is functional, it has a purpose.

Functional training comes to us from the sports medicine world. The idea was that exercises that will help an athlete to come back from an injury are probably also the sorts of exercises that will help to maintain and improve health. Go figure.

The evolution of this idea means that a training program “should carefully blend concepts and knowledge from areas such as sports medicine, physical therapy, and sports performance to create the best possible scenario for that particular athlete”. (Mike Boyle, New Functional Training for Sports, 2nd Edition)

Functional training is widely misunderstood to mean “sport-specific training”; suggesting that certain movement patterns are unique to certain sports or activities. The thing is, just about all “sport-specific” movements are some combination or variant of the basics…

…where “the basics” represent the movements that are possible at any given joint in the human body.

In this way, functional training becomes quite similar for every body and every sport (or performing art).

Some (many) have come to view “functional training” as having clients and athletes lifting weights on balance boards and balls.

As an aside, this is a seductive idea: if you can train yourself to lift things or do things while balancing on something unstable, it seems to make sense: your core will be challenged, your balance will improve and, for circus artists, it’s just like being on an apparatus…it’s so “functional”! If it works for people with injuries and post-stroke patients, it’s good enough for me!

The only problem with that is training on unstable surfaces has been shown to reduce force output (which is not helpful if your goal is to develop strength or power)…

And, it doesn’t actually transfer very well to the field/floor/trapeze.

The key to this particular aside is that it is really helpful to be very clear about what your training goal is: if you’re doing exercises on a wobble board and you happen to be developing a rolla-bolla act, then you could be in luck…but you should know that you’re probably just “practicing” and not “training”. If, on the other hand, you’re looking to improve strength and dynamic stability, there are actually better ways to go.

And for some (many), functional training means only training multi joint exercises with a full range of motion.

The trick here is that “function varies from joint to joint”.

Function varies from joint to joint.

Mike Boyle

Some joints need to be mobile, able to express a full range of motion and thus, require developing strength through that range of motion.

Other joints, however, tend to require stability more than mobility.

If we pause to think about it, this makes complete sense: the stable joints provide a platform from which the mobile joints can perform. Consider your arms and shoulders. Your rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers must be sufficiently strong so that they can provide a base for the actions of your arm. You can actually follow the chain back down to the original stabilizer: your core.

This is where functional movement and corrective exercise come into play.

So what is functional movement anyway?

Well, I am not talking about primal movement or any sort of animal flow-type thing here. These sorts of things have the potential to be great…but for many humans out there, we’re more likely to end up moving poorly or creating/aggravating an injury because their bodies just are not ready for this kind of exercise (which is actually my whole point here).

The foundation of all functional movement is having a balance of the joint mobility and stability required to express the basic human movement patterns with integrity.

The foundation of all functional movement is having a balance of the joint mobility and stability required to express the following basic human movement patterns with integrity:

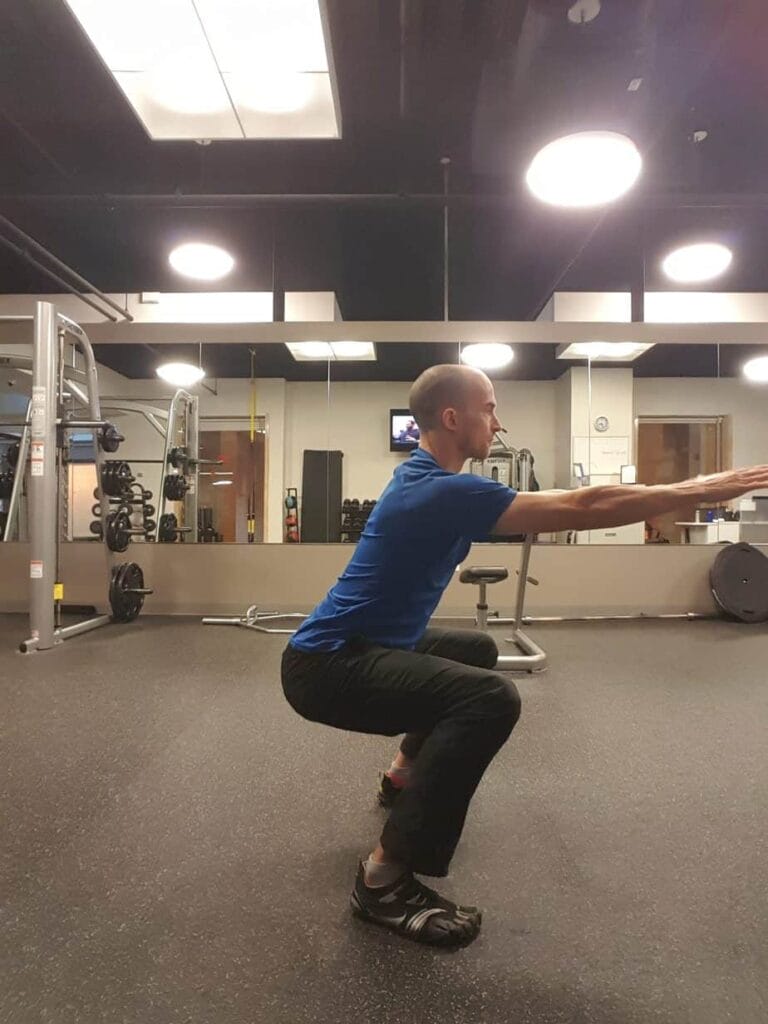

- Squat

- Hip Hinge

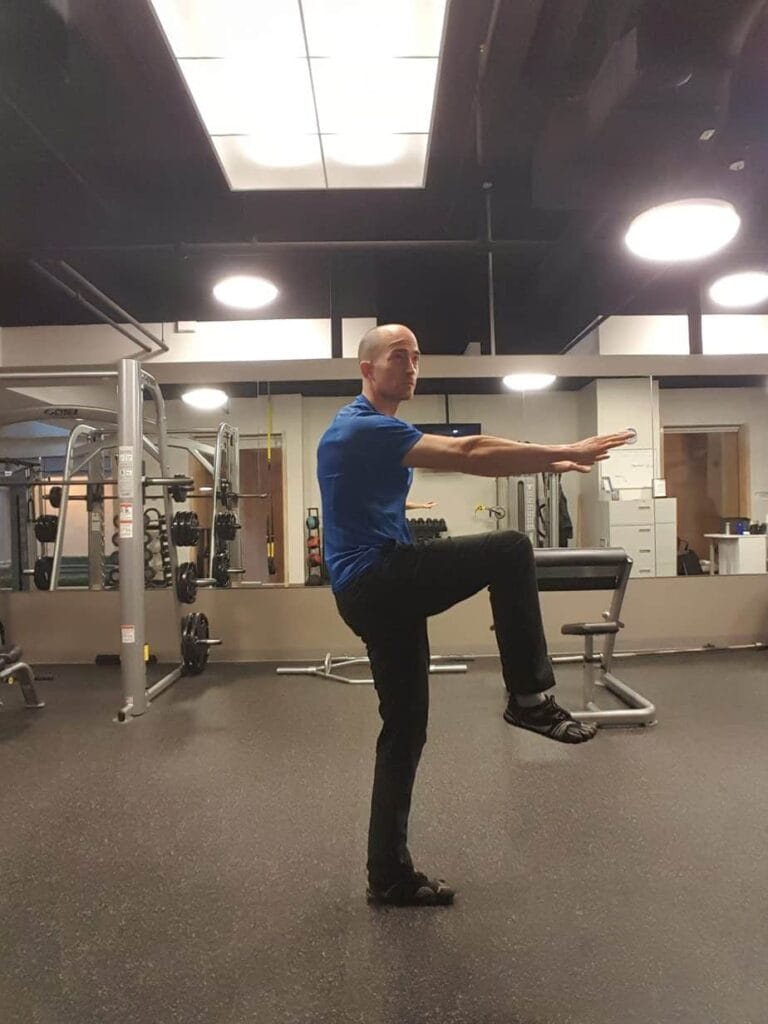

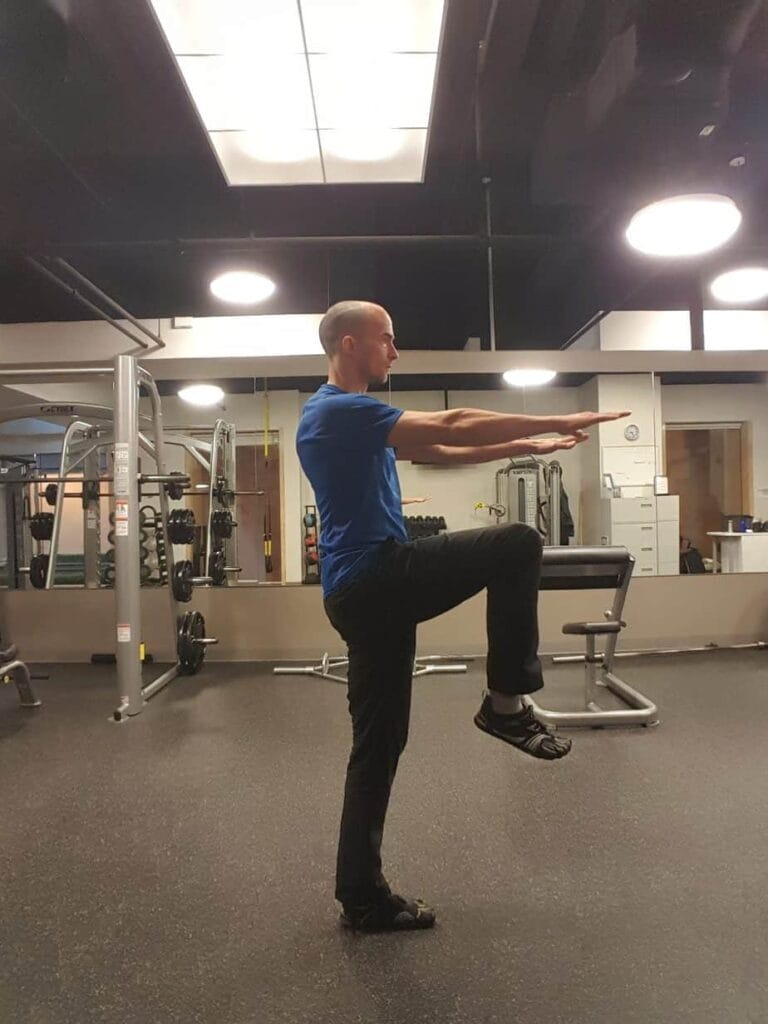

- Step

- Lunge

- Horizontal Push and Pull

- Vertical Push and Pull

Functional movement simplified

Let’s dig deeper: what does it mean to have the “balance of the joint mobility and stability required to express [those] basic human movement patterns…”

It means, can you (or someone like you) dissociate (move independently of each other):

- Scapula and Cervical Spine?

- GH Joint and Lumbar Spine?

- Femur and Pelvis?

- Femur and Lumbar Spine?

…and do it “with integrity”?

(Credit goes to Kevin Carr of Movement As Medicine for this elegant summation of functional movement.)

Essential to the concept of functional training is learning to move before you load.

Mike Boyle, New Functional Training for Sports, 2nd Edition.

This could really be oversimplifying (except it’s not, really) but one particularly powerful indicator of whether someone (like you?) can perform a movement with integrity or not is whether they (you) can breathe normally as they move.

In particular, can they (you) breathe normally (while maintaining form) at end-range?

Or when performing the movement under load (again, while maintaining form)?

That’s it. It’s that simple.

Can you shrug your shoulders without moving your head/neck?

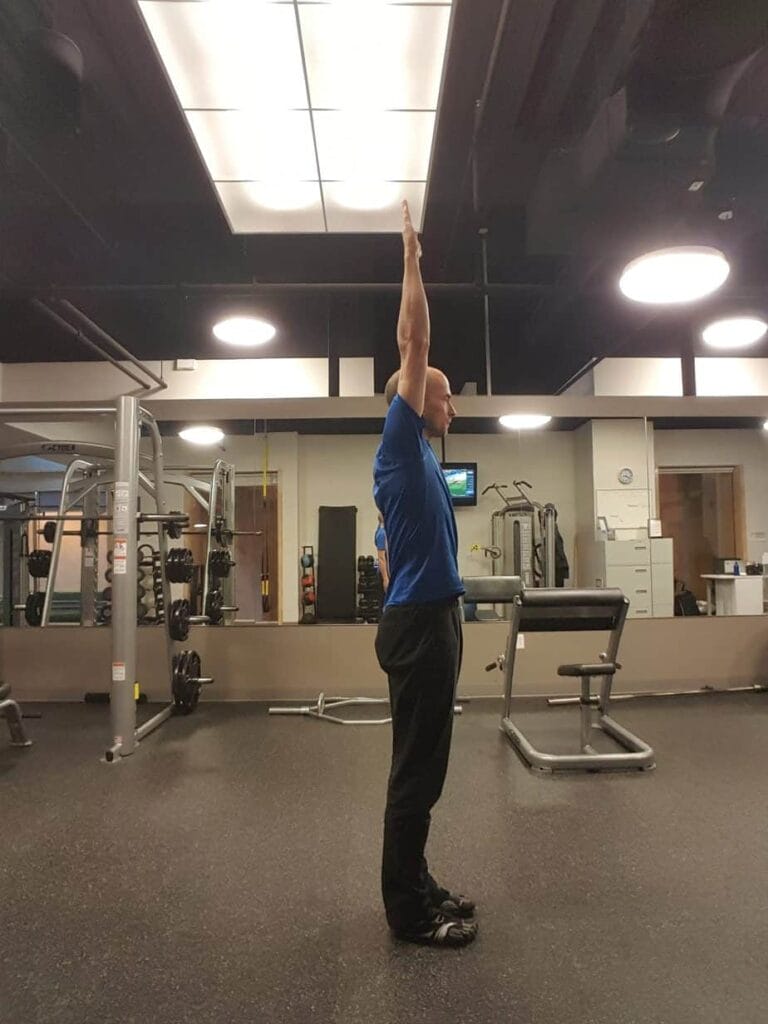

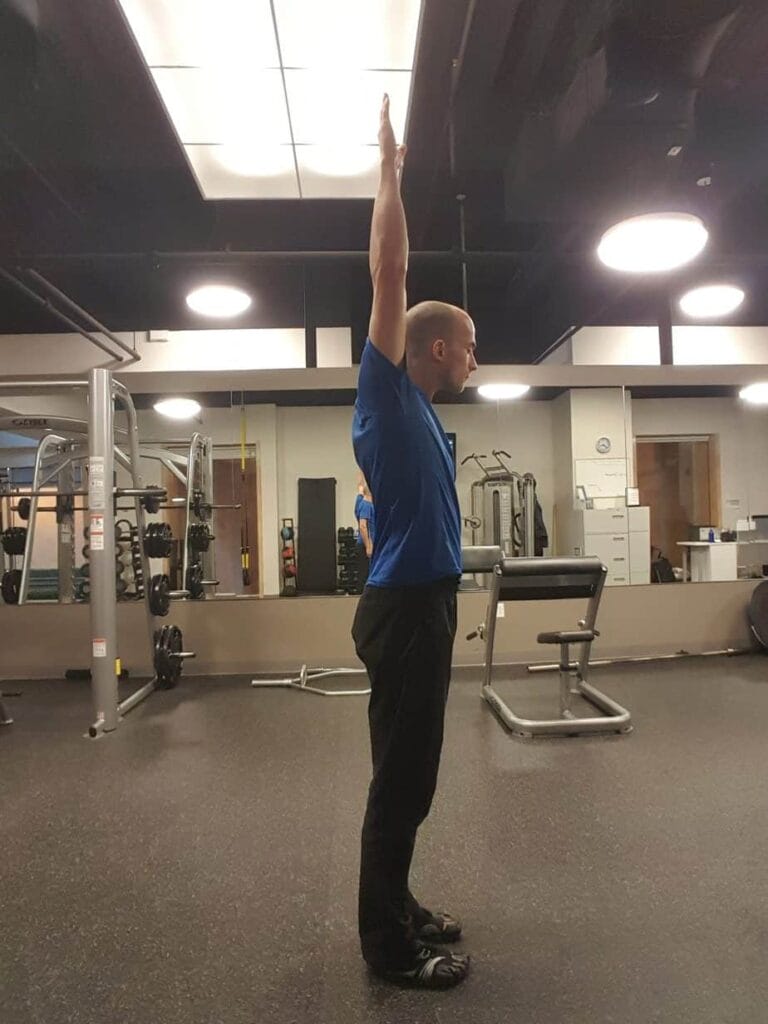

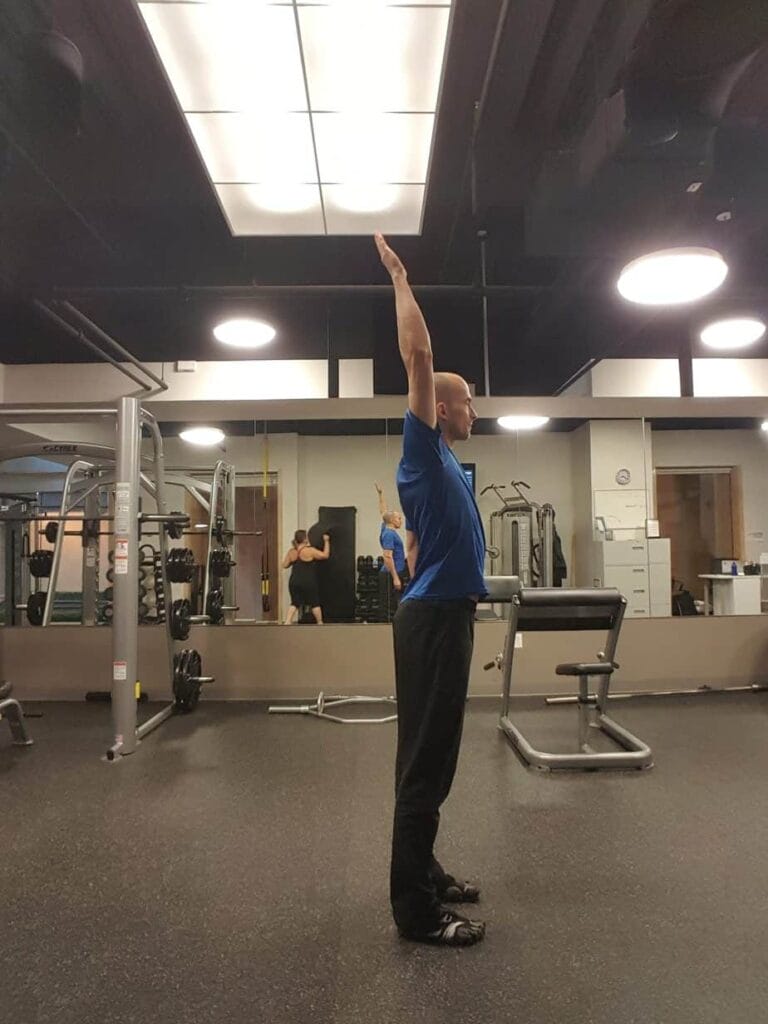

Can you raise your arm all the way overhead without arching your lower back?

Can you bend at the hips without tilting your pelvis? Without moving your lower back? Can you do both of those things one leg at a time?

(And lately, I’ve been thinking that it’s important to be able to dissociate movement of your thoracic spine from your lumbar spine. Meaning, can you keep your lumbar spine still while creating movement with your thoracic spine?)

If you can do those things, that’s functional movement. For. Every. Body.

And, what do we do with functional movement? We train it and make it really strong.

And that’s functional training.

References:

New Functional Training for Sports, 2nd Edition, by Mike Boyle

History of the Functional Movement Screen, by Lee Burton

Pingback: Squeeze your glutes! But what if you can’t squeeze your glutes? | Get Circus Strong

Pingback: Squeeze your glutes! But what if you can’t squeeze your glutes? - Reimagym