[alert type=”info” close=”false” heading=”Just a quick note to the reader…”] While I have made an effort to keep my use of jargon to a minimum, this post is pretty heavy on the geekery. Because it is a part of an extended thought that I’ve been having, it is also on the lengthy side. In theory, a good blog post has a substantially lower total word count than this…but this is my fundamental dilemma: I could just tell you ‘hey, do it this way’, but without the underlying why, we miss out on an opportunity for deeper understanding and reflection.

So, if you’re up for it, get comfy and enjoy. I’ve split this into two parts because part one took six pages…[/alert]

I recently had the pleasure of attending the 2018 Winter Seminar at Mike Boyle Strength and Conditioning in Woburn, just north of Boston, MA. It always feels a bit like coming home whenever I visit MBSC. That’s a testament to the sense of connection and community they’ve created for not only their clients, but for all of us in the Certified Functional Strength Coach family (MBSC is where I did my cert a couple of years ago). In Coach Boyle’s presentation, he reminded the audience of his maxim: ‘Steal Smart People’s Stuff’.

So, to that end: everything I’m about to share with you is a synthesis of stuff I learned (stole) from people much smarter than me.

That’s the whole point to this coaching thing, though: it doesn’t really matter whose idea it was (it’s nice to give credit where it’s due, of course); what matters is whether it means your athletes get better results.

The results I’m talking about here are injury reduction and performance enhancement.

Injury Reduction

I haven’t even gotten to the good stuff yet and I’m already off on a tangent…

I know that injury prevention is the term that’s most used and most familiar, but there is a growing trend in the strength and conditioning world to use the term injury reduction. Athletic pursuits very often involve pushing yourself to the edges of your current physical (and mental) capacities. And make no mistake, while there’s no doubt circus is art, it’s performing art with some very high physical demands, so it’s also an athletic pursuit. Regardless, sometimes in the process of exploring the edges, you go a little beyond the edge.

Injuries happen.

And certainly, the goal is to prevent injuries that don’t have to happen in the first place, but for the rest of those eventual wanderings into the places beyond your current limits, the goal is to mitigate the potential severity of the injury.

If it’s going to happen, let’s make sure it’s not that bad.

This is a big thought that deserves more attention—later.

Performance Enhancement

Is it ok for me to call it performance enhancement?

I think that in most cases (in a circus context, anyway), we tend to think of performance as what happens when you have an act that you’ve been rehearsing and then you perform your act to your chosen music (or to the music playing in the club at that point in time) and there’s a crowd and possibly some mood lighting.

In this context, however, performance enhancement means doing things that will make you—your body and your mind—perform (do) better in your circus arts discipline-of-choice. It means optimally preparing your body—and your mind—for the training session you are about to do.

I think that it’s actually quite important for us to be thinking in terms of optimizing physical performance because that is the key to being able to improve and grow and to being able to continue to do so for an extended period of time—ideally, for many years to come.

Sometimes I encounter a perspective that says ‘optimally preparing your body’ sounds too serious when all we want to do is have fun. If you’re reading this, I’m assuming you’re over that…if it was ever a thing for you at all.

So, getting back to the stuff I learned from other smart people:

Let’s Rethink the Warm-up

Maybe the easiest place to start is the name: the warm-up. Calling it that is fine…except that it tends to have a lot of folks focusing on the warming up bit.

The increase in tissue temperature.

The main idea that I would like to convey is that, yes, it is important and useful to increase tissue temperature prior to training.

Raising tissue temperature makes muscles function better, contracting faster and more forcefully…

Increased tissue temperature reduces viscosity making joints move more smoothly…

Yes to all of those wonderful, physiological benefits of literally warming up your muscles and ligaments and tendons and joints.

However, the “warm-up” also presents us with a fantastic opportunity to do so much more than just (literally) “warm up”.

We have an opportunity to manage relative stiffness, optimize movement and to prepare, focus and hone body and mind for the work ahead.

In the ideal case, we would be able to address individual needs with our exercise choices but designing an individualized warm-up sequence isn’t a luxury available to everyone. Nevertheless, there is a lot of room to make even generalized group warm-ups more effective.

We Could Be Getting So Much More Out of “The Warm-up”

Any maybe you already are, but just in case (I mean, you have read this far already), here’s the backstory to my thought:

I was recently reading through a case-study in my favorite bedside tome—Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes, by Shirley Sahrmann—and in summarizing the initial diagnosis, Sahrmann noted the following “Flexibility and Stiffness Impairments”:

The lumbar spine is more flexible into extension than either the counteracting tautness of the abdominal muscles that tilt the pelvis posteriorly or the anterior supporting structures of the spine that limit extension. The hip flexors are stiffer than the abdominal muscles that tilt the pelvis posteriorly. The latissimus dorsi muscle may also be stiffer than the abdominal muscles and contribute to excessive lumbar extension.

—Sahrmann, Shirley. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes (Page 90). Elsevier Health. Kindle Edition.

And that all got me thinking of one of Eric Cressey’s presentations on managing good and bad stiffness (from Functional Stability Training: Optimizing Movement if you’re interested).

Relative Stiffness

Stiffness applies to muscles, tendons, ligaments and fascia. For the purposes of this post, I will focus on muscular stiffness.

Stiffness generally refers to the passive tension in a particular tissue. Muscle tension can result from a variety of factors—neural tension (usually a product of increased sympathetic activity), for example. One factor that is particularly relevant to this train of thought is training.

The more you use (develop/strengthen) a muscle, the more stiffness it will develop. And the less you move a joint, the more stiffness the closed (shortened) side of the joint capsule will develop.

This is not, by the way, a reason to avoid strength training. That whole ‘strength training will make you less flexible’ notion is hornswoggle. Nonsense. Balderdash.

While the muscle you train will become stiffer, this is actually the whole point to this post: how you train your everything-else will dictate how the overall balance of stiffness plays out in your body and how it moves. Everything has context: if your training plan isn’t appropriately balanced or only includes resistance training and does not include functional mobility work, then yes, you are going to develop some stiffness. Some of it will be good. Some of it might not be so good.

Which brings me back to this key concept:

The stiffness in any one area/joint of the body influences how adjacent joints move—or don’t move—based on which joint has more or less stiffness controlling it.

For example, hip extension.

To fully extend your hip joint—without compensatory movement from your pelvis and low back—your abdominal muscles need to have more stiffness than your hip flexors and your low back extensors. (Something you can see I need to work on, based on the video above).

[pullquote type=”right”]The stiffness in any one area/joint of the body influences how adjacent joints move—or don’t move—based on which joint has more or less stiffness controlling it.[/pullquote]

Why?

Because if your hip flexors are more stiff than your abdominals, they will resist the stretch that happens when your hip tries to extend. That means as your femur moves back, your hip flexors will pull on the front of your pelvis, tipping it anteriorly.

Why does this even matter?

I’m sure you can imagine that there are many skills and/or movements in circus that ask you to fully extend your hip. In fact, extending your hip past neutral is technically hyperextension of the hip. Like anytime you do a split. Or a gazelle. Or a croc.

If you are unable to fully extend your hip, your body will need to compensate by arching through your lower back. This places extra stress on the intervertebral discs of your lower back. Since another popular compensation here is to roll your hip out (i.e., a non-squared-hip split), this produces a torque on the spine which can place extra stress on the facet joints of your lower back.

Over time, these stresses are the kinds that tend to lead to lower back pain. As a reminder: just because you damage a disc or strain a facet joint, doesn’t mean you’ll have pain. As folks get older, it becomes increasingly common for there to be some degree of degeneration within an intervertebral disc or two…and often, they do not experience pain.

Unless they don’t move well…then pain might be more likely.

Really, sub-optimal movements and imbalanced stiffness don’t always result in pain…until they do.

However, if we circle back to the beginning: I like the idea of making training choices that mitigate the risk of developing or worsening low back pain (or any kind of pain, really).

I should re-phrase that: the number one priority for me as a strength coach is do no harm. That’s why being aware of how relative stiffness influences movement matters.

How about another example? Overhead shoulder flexion

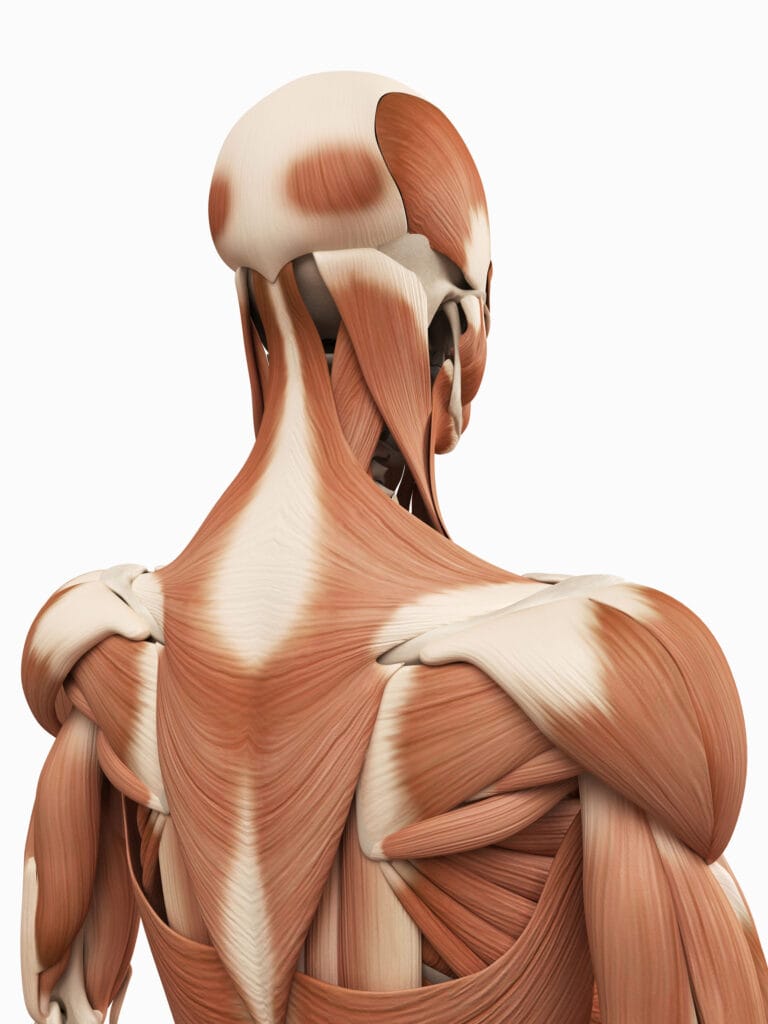

To flex your shoulder fully overhead while maintaining a neutral core position (meaning without rib flare/arching through the low back), the stiffness of your anterior core (rectus abdominis and external obliques in particular) must be greater than the stiffness in your lats.

Why?

Because if your lats are stiff (and, if you do aerial or flying trapeze, chances are your lats are stiff because they get lots of use from all that pulling down), they will resist lengthening. Left unchecked by the anterior core, they will encourage your lower back to arch as your arms go overhead. However, if your anterior core has more stiffness than your lats, then your lats will be more apt to lengthen while your lower back stays in position.

Why does this matter?

Arching through your low back—and not achieving 180° of flexion—means two things:

One, as I outlined in the hip example, it means that extra stress gets transmitted though the discs of your lumbar vertebrae. Over time, that’s just not going to be a good thing.

Two, and probably the one you’ll “feel” sooner, this means extra stress on any or all of the structures that make up your shoulder joint, such as your rotator cuff or labrum.

Well, it’s actually a bit trickier than that. We could also discuss the ever-popular forward head posture (which I like to call “the turtle”) and the impact that has on your neck. And we haven’t even begun to discuss how differences in stiffness between your upper traps, lower traps and serratus anterior can impact scapular mechanics.

Managing Relative Stiffness

With the idea of relative stiffness in mind, it is probably beginning to seem obvious that we want to make exercise and training choices that reinforce or enhance good stiffness (stiffness where want stiffness) and reduce bad stiffness (in places where we don’t want as much stiffness).

Stiffness is a funny word if you type it out enough.

In a way, your entire strength training plan could revolve around the idea of managing relative stiffness.

But the central thought I had started all of this with was how we can use the warm-up for a few things, but one of the more significant things we can do is to reinforce the good stiffness and reduce the bad.

The question now is “how?”

That’s what part two is all about: now that we’ve described relative stiffness, next we can discuss how we can manage it in our warm-ups.

Pingback: Geekery: Relative Stiffness and the Warmup (part deux) | Get Circus Strong