I want to talk about breathing this month. Sure, we all do it, but are we doing it effectively? Most specifically, are we breathing optimally while exercising or training. Making sure we are breathing optimally will ensure we are strong and less likely to injure ourselves.

Over the years I have had many students or clients say something to the effect of ‘breathing in this move/exercise is hard’, or ‘I can’t seem to get the breathing pattern right.’ Breathing during a physically demanding movement is challenging and I get it. This post is about how I help my clients and students learn the correct breathing patterns (and hopefully it will help you, too!). As part of this learning process, I also aim to teach them (and you) why these breathing patterns are so important.

The Breathing Struggles

Contracted Core

First let’s look at why breathing can be difficult while exercising or during your training activity: your core is (hopefully) contracted. I say hopefully because not every one out there doing physical activity is contracting their core or contracting it correctly. Your core is your center and where all movement begins and its job is to protect and stabilize the spine in movement. If you have been in any of my classes or training sessions, you probably have heard me refer to the toy from the 50’s (maybe earlier than that) where you pulled the string that runs through their center and the arms and legs move. (see below)

I like this illustration because it shows our core is involved in everything we do: siting, standing, walking, reaching, moving things, jumping jacks, etc…….

We need the core to be working effectively and that generally starts with our breathing. When we shift from daily tasks to training exercises then we need the core to contract and create more stiffness than the other muscles involved in the exercise we’re doing to ensure spinal stabilization. This ensures spine safety and decreases the likeliness of injury.

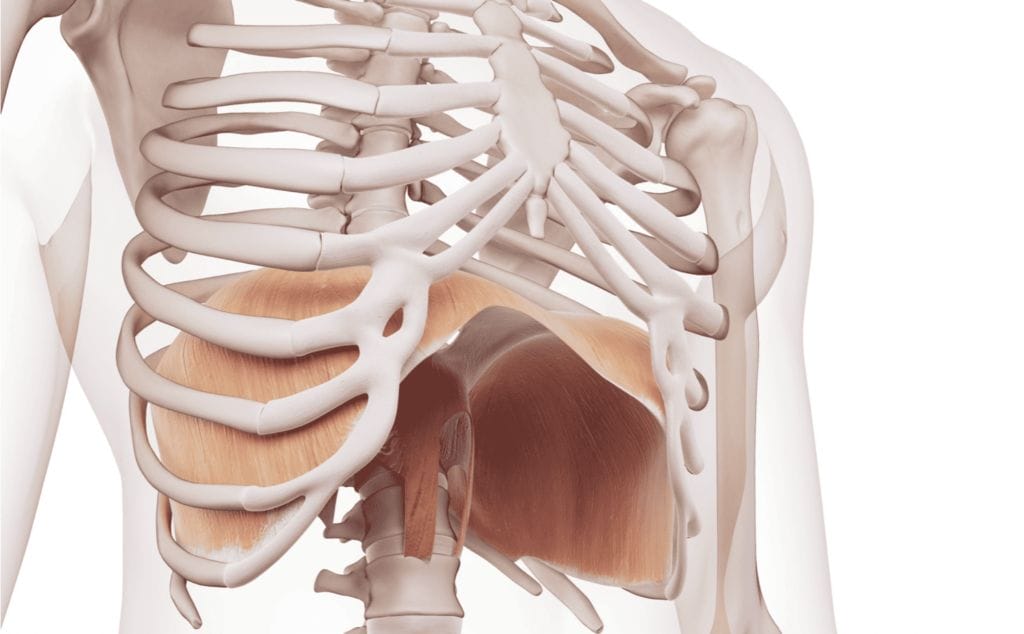

So why does contracting your core with more effort, like during a plank, push-up or hanging leg lift, come with the increased challenge of keeping your core engaged and continuing to breathe? Well, that’s because your diaphragm–your major breathing muscle (see photo)–is the very top of your core. When we engage our core, we should be engaging our deep core muscles (diaphragm, transverse abdominis and pelvic floor) and then the more superficial core (obliques and sometimes the rectus abs).

Breathing and your core

When inhaling, your diaphragm contracts and presses down into your abdominal region making more room for your lungs to expand into as they take in oxygen. As the diaphragm presses into your abdominal region, this makes your belly rise up or expand out, which can be hard to do if you have contracted all the muscles in your abdominal region.

A great way to reset your breath and get your diaphragm moving is with some 90/90 Belly Breathing first. This breathing technique as a focus on the exhalation and the contracting of the abs at the end phase of the exhale to assist the diaphragm pushing the air.

Practice this breathing technique first and get this one down first before moving on. This can be done daily or several times a day to help reset your breathing and a great way to relax.

After the belly breathing feels good I generally instruct clients or students to try to breathe laterally into their ribs as a way to not disrupt the contraction happening within the abdominal region. This lateral breathing can take practice. Here’s a video explaining it.

The reasoning behind offering this kind of breathing is that focusing on breathing into your rib cage and expanding the ribs out to the sides (and even to the back of the ribs) usually helps people be able to continue to engage their core and be able to breathe simultaneously. As I said earlier, most people find it hard to engage their core and still breathe and then they either hold their breath (not good on so many levels: oxygen depletion, rise in blood pressure to name a few) or when they take a breath, they lose their core contraction. This is also not ideal as it will put you at risk for possible injury.

Here’s a great video explaining the lateral breathing used during pilates, which is also where I first learned it-in my pilates certification.

More and More Challenging….

Of course as you gain strength and control in your core musculature, the breathing can take on more of a 360-degree breath where you breathe a little bit everywhere. This means sending the inhalation a little in your belly, your back, laterally in your ribs and into your chest and upper back. This 360-degree style of breathing will also take practice. Here’s a video I found that I like.

Putting it to Work

Try breathing into your ribs while performing plank or side plank, hollow body, push-ups, squats or single-leg dead lifts (to name a few options). Again, this will take time and practice. Keep working at it.

Once you get the hang of breathing with a contracted core, it’s now time to check whether you’re breathing at the correct time while performing the exercise.

Breathing Pattern

So now you have your contracted core and you can breathe while performing a (insert exercise here). Excellent! Now let’s check in on your pattern. More often than not, while exercising you should exhale on exertion. For example, when pushing up away from the floor in a push-up or when pushing up away from the floor in a squat.

To get into some more circus specifics, you want to exhale if you are doing hanging leg-lifts or when you are straddling up, or any inversion. If you are doing pull-ups, exhale as you pull up, this is because this is harder, however if you are training pull-up negatives (to get your pull-ups some day soon) then you would exhale on the way down, because you are only focusing on the lowering phase in this exercise.

Now the reason for this is when we breathe in, our belly and lower ribs naturally expand to make room for the inflation of your lungs. When the ribs expand out this flares the lower ribs a little, which is opposite of what is wanted when we are engaging our core and drawing everything in towards the spine to keep us protected and stable (contracting your core is not sucking in your stomach, this doesn’t really contract your muscles in a way that is going to protect your spine.) Flared ribs indicate loss of core tension (AKA contraction) which also looks like an arch through the spine. With this arch now not only is the spine strained; the core contraction is compromised or gone.

On the other side of the breath, when we exhale, the ribs and abdominal region move in towards the spine and this is a way more ideal place for core contraction. That’s why when contracting your core you should do it on an exhale. This natural drawing down of your ribs and abdominal region on the exhale is perfectly harmonious for where you need your body to be when exercising with an engaged core.

Applying This to Exercise

Let me use the push up as an example. As you can see from the photos below the starting position is a strong plank shape: a line can be drawn from the ears through the shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. The lowered position, nothing changes, only the elbows bend. (There is some accessory movement of their scapula, but I usually don’t focus on this as a coaching cue at first). This is an example of a great push-up demonstrating breathing properly, inhaling on the way down and exhaling on the way up.

Now let’s look at some push-ups that, for this post, are demonstrating generally what someone looks like they’ve lost their core tension (AKA contraction) and they’re probably breathing in reverse: exhaling on the lowering phase and inhaling on the pressing-up phase. Of course, a person can look like these not-so-great push-ups even if they are exhaling on the press up (exertion) phase, but I want to use these photos to illustrate how an inhale might compromise the core tension and create flared ribs and an arch in the back, putting lots of stress into our spine.

Bringing it all together

The takeaway is that you want to get really good, through regular practice, at being able to contract your core while breathing. Start with practicing and mastering belly breathing. Then you can practice lateral breathing with that slight core engagement from the video above. When that feels good, work on your core contraction with the lateral breathing (expanding the rib cage sideways), first while seated or lying down without exercise and then take that lateral breathing to less demanding exercises: pilates toe taps or pilates ab prep. Then move on to planks and side planks as these exercises require you to engage your core, but you are not moving any part of your body so you can really focus on the strong core engagement while breathing.

Once you have that you can begin to add exercises that have movements: dead bugs, push-ups, squats, lunges… Make sure to exhale on the exertion to keep your body in the optimum position for performing the exercise.

Practice these breathing techniques on their own and with exercise and become aware of your breath in your training sessions. Notice when you lose your core contraction or when your ribs start to flare or when you’re not exhaling on exertion. Then pause, reset and begin again. If you can’t maintain good core contraction and proper breathing, call yourself done with that exercise level of challenge and try an easier version of that exercise. If that doesn’t work, maybe try an entirely different exercise. If none of those options help, you may be done training for the day. It is better to be safe than risk potential injury.

As always, I love hearing from you. If you have any questions or are interested in training with us, please contact us.

Be Well,~~Theresa

Pingback: Improve Your Training Results with Your Breath – Redefine Strength & Fitness

Pingback: 5 Questions to Ask Yourself About Your Hips – Redefine Strength & Fitness

Pingback: What’s Your Ribs Got To Do With It? - Redefine Strength & Fitness

Pingback: 2 Core Activation Exercises Every Circus Athlete (and everyone else) Should Be Doing - Redefine Strength & Fitness

Pingback: 5 Questions to Ask Yourself About Your Hips - Reimagym

Pingback: Why we do ‘agility’ ladder drills - Reimagym